Twenty-twenty was an excellent year to be an archaeologist. Direction from the CDC that we gather only outdoors, and that we maintain social distance required only minor tweaks to excavation protocols. Over the last 15 months, Colonial Williamsburg’s archaeologists have charged ahead, spreading out across four acres to excavate Custis Square, test the Raleigh Tavern lots for a possible future return, and begin a high-profile excavation on the site of the First Baptist Church. These are heady times.

Twenty-twenty-one promises to extend the streak. Last month, Netflix shone a spotlight on archaeology with the release of the movie The Dig, a British drama centered on the 1939 excavation of a Viking ship at Sutton Hoo, a medieval site near Woodbridge, in Suffolk England. Although I have not yet seen the film, I am told that the archaeology is interesting, but that the more compelling story revolves around the archaeologists.

This comes as no surprise. In fact, 2020 brought me to this same epiphany in a somewhat roundabout way.

I have spent part of this pandemic year hunting down Colonial Williamsburg’s archaeological forebears—a rabbit hole into which I descended while doing preliminary research on the sites mentioned above. This journey began in Colonial Williamsburg’s John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library’s Visual Resources Collection, among stacks of black and white photographs documenting the early restoration.

When they include people, these images are infinitely more interesting. One of my favorites, for example, is this image of the Governor’s Palace cellar under excavation in 1930. Two men in light-colored suits pose in the center, impractically dressed for the occasion, and looking out of place. This dapper duo likely includes Prentice Duell, an Egyptologist borrowed from the Sakkarah Expedition, and either John Etheridge (the site foreman), or Herbert Ragland (the project’s field supervisor). Their names can be found in the final archaeological report, produced to summarize the project and its findings.

This image includes 16 additional men — Black excavators — whose identities are less clear. Unlike the center figures, they have not stopped to be photographed. Many are in motion, pushing wheelbarrows full of brick rubble. Daily work logs reference them only in the collective: “27 men” worked on July 18; “46 men” on August 1. Their names are not recorded.

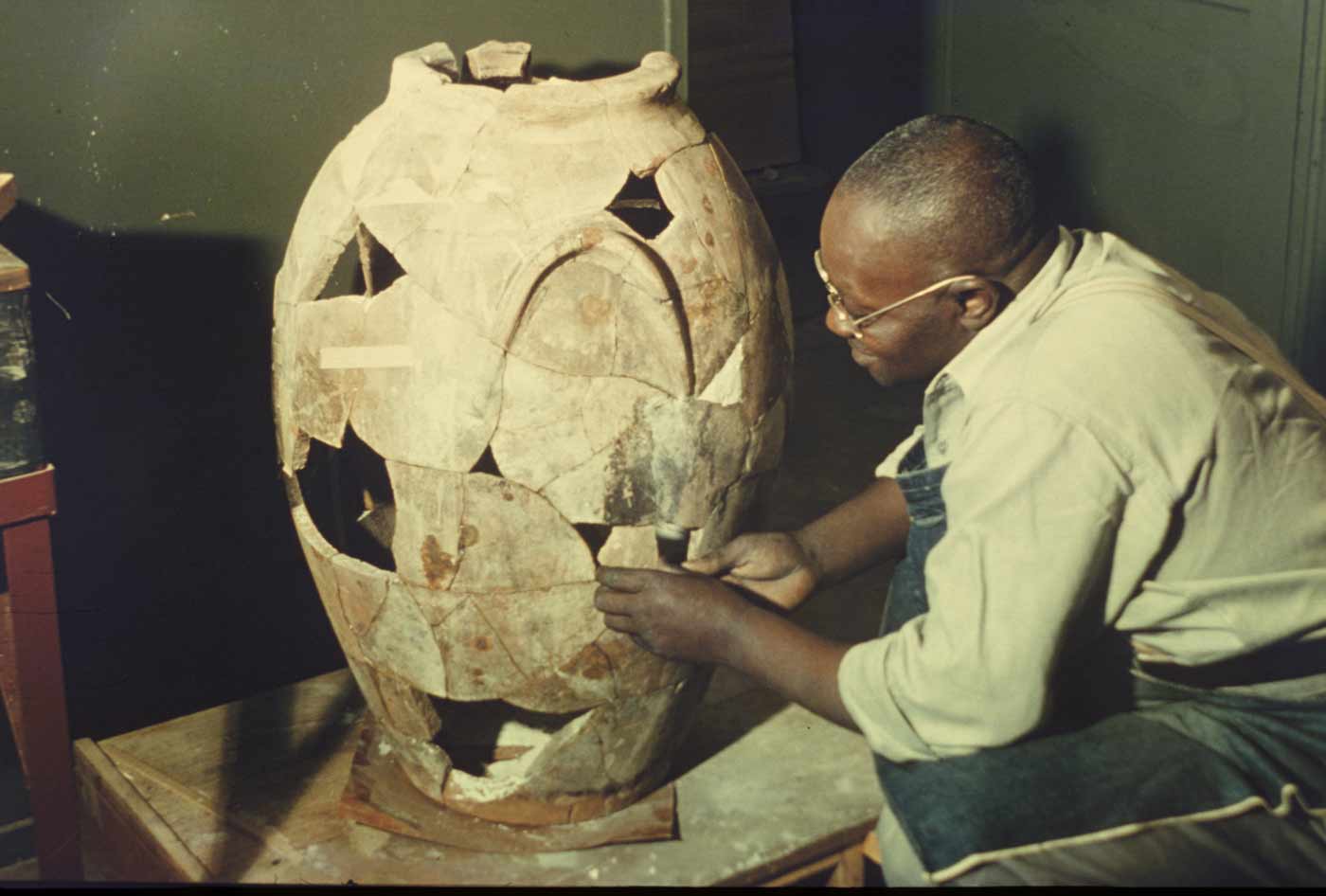

The Palace project is not unique in this regard. Images in the Foundation’s collection reveal that between 1928 and the mid-1960s, the excavation of 18th-century Williamsburg fell primarily to Black men. Hired as general laborers, they systematically recovered hundreds of brick foundations, enabling the reconstruction of houses, shops, and outbuildings. Some of them continued in this work for decades, making the transition from early trenching techniques to the careful stratigraphic excavation implemented around 1960. In images, a distinctive chin, a favorite field hat, or a penchant for wearing suspenders make a few of these men familiar, but we have no names.

Among other “pandemic projects,” the last several months have afforded an opportunity to dig deeper into the identities and the stories of these groundbreakers. Several sources of information have been tapped for this mission — The Colonial Williamsburg News, and the Foundation’s corporate archives, among them — but the most complete and vivid stories have come from two interviews with early Black excavators themselves. Linwood Williams and James Christian were interviewed by archaeologist Andrea Foster in the early 1980s as part of an oral history project. The deteriorating cassette tapes on which those stories were captured were rediscovered by Dr. Ywone Edwards Ingram around 2010, and converted to digital file format, but it was not until William and Mary undergraduate Eleanor Renshaw transcribed the interviews last fall that the experiences of Linwood Williams and James Christian became accessible.

Linwood Williams is undoubtedly among the men depicted in the Palace images. He began working for the restoration in 1928 as an employee of Todd & Brown, the contracting company that oversaw early excavation. Williams participated in excavations at the Capitol, the Wren Building, the Wythe House yard, and a property he refers to as the Prentis Store, but which we know today as the Archibald Blair Storehouse, home to the recent “Kids Dig.” The Palace project fueled Williams’ most detailed memories. He recalled excavating the Revolutionary War burial ground, and re-establishing the Palace canal which, by 1930, was a swamp. More than 50 years later, he was able to provide names of those he dug alongside: Charlie Banks, Paul Walker, and his brothers, Eddie and Wallace Williams.

Like many early excavators, Williams’ job classification was as a “laborer,” a position defined by tremendous fluidity. During the museum’s earliest years, an emphasis on finding brick foundations required most “laborers” to be assigned to excavation tasks. As the pace of discovery slowed, excavators were reassigned to construction crews, and later, to gardening and landscaping duties. Linwood Williams’ 50-year career followed this trajectory. Hired in 1928 as a “foundation digger” (his words), he retired in 1978 after 34 years as a gardener. He was proud of having planted the trees in the Capitol yard, as well as those surrounding the Williamsburg Inn.

James Christian began working for Colonial Williamsburg around 1950 — nearly a generation after Williams. In his interview, he was more guarded, and while he offered fewer detailed memories of the excavations in which he participated, James Christian recalled that he worked on the site of the First Baptist Church in 1957. It was a watershed year for Archaeology. In 1957 the arrival of Ivor Noel Hume as the first Director of Archaeology would spell new goals and methods for the excavation program; the architectural trenching technique in which Christian had become proficient, would soon be abandoned. James Christian was one of the last excavators to work for “Jimmy” Knight, an architectural draftsman whose name has been inextricably linked to the trenches he employed. Like Linwood Williams, James Christian had a long career at Colonial Williamsburg, gathering experiences in the areas of building maintenance and construction. He referred to his time as an excavator as “the good old days,” and was especially appreciative of co-workers “Old Man Gray,” and “Manuel” both from Lackey, and “Charlie from Grove.”

The names and accomplishments of other remarkable individuals have been pieced together from scattered records. Daniel Louden, hired in 1948, was described as one of Ivor Noël Hume’s “most valuable excavators.” Identifiable by his distinctive field hat, Louden appears frequently in archaeological images from the 1960s and early 1970s, including those documenting the excavation of Wetherburn’s Tavern, the Geddy foundry, and the 1964 excavation at Custis Square. Louden successfully navigated the transition from trenching to stratigraphic excavation, the latter, a skill he honed despite annual seasonal furloughs to the Landscaping Department. In 1972, he marked 25 years of service with Colonial Williamsburg. Daniel Louden was identified as a gardener when he retired in 1975.

Thomas Banks was hired in 1960, and often appears in images alongside Daniel Louden. In 1971, Banks was made an Archaeological Foreman, but along the way, held positions as a kitchen helper, gardener, laborer, janitor, and an archaeological excavator.

There were innovators among these early archaeologists. During the winter of 1960, excavation in the streambed at the Hay Cabinetmaker Shop was made slightly less miserable by Paul Ellis’s suggested use of a motorized conveyor belt to move mud uphill, and away from the excavation. The Suggestions Committee gave Ellis an award for his time-saving idea.

Sandy Morse found his niche in the lab. Hired as a laborer in 1947, by late 1954 Morse was working with artifacts: numbering ceramics, and mending vessels. It is his handwriting that keeps us straight when working with early ceramics collections. Morse indexed office collections of creamware and delftware and built stands for display cases. In 1955 he was given the title “Junior Archaeological Treatment Assistant,” a position he retained until his retirement in 1960.

These stories are just a sampling of those we have uncovered. To date, the names of more than two dozen Black excavators, hired before 1965, have been identified. Although some continued to work on archaeological sites beyond the mid-1960s, many of the experienced, self-taught men occupying excavator positions found themselves squeezed out by the increasing professionalization of a new discipline called Historical Archaeology. College students began to fill the role of “summer hires,” and when men like Daniel Louden retired, they were replaced by candidates with academic credentials. Although Historical Archaeology has taken exciting directions since its inception in the early 1960s, the loss of experience embodied by our predecessors is profound.

Where do we take the story from here?

The goal of this initiative — to identify excavators by name and to acknowledge their contributions — has shifted over the last several months. Instead of asking “who are these men?”, a better question for this moment seems to be “who are these men to us?” Where do they fit into our archaeological origin story? Do we call them archaeologists?

For as long as I can remember, Colonial Williamsburg’s archaeologists have diligently distinguished trenching (1928-1957) from “real” Archaeology (1958-present). These practices are, indeed, different. But in defending the distinction, we have simultaneously dismissed individuals engaged in that work. The terms “laborer,” “day laborer,” and “unskilled labor,” have been thoughtlessly applied to early excavators in written histories of Williamsburg’s archaeological program — including some by this author — suggesting lack of investment, skill, or care.

Of course, this is not true.

The interview with Linwood Williams reveals that he was skilled in differentiating not just the forms, but various functions, of outbuildings. And half a century later, Williams was still pondering indicators that made it possible to distinguish male skeletons from female in the Palace cemetery. These are not the marks of a disinterested man. There is also evidence in interviews and images that the careless techniques we ascribe to early excavation are unfair. Trowels and brushes are described alongside the more aggressive shovels and picks that we typically associate with trenching, and there is ample evidence of the use of screens to recover artifacts. Trenching may have gotten a bad rap, but “trenchers,” even more so.

These are men who moved the archaeological ball forward. Before archaeology had even been assigned a role in exploring “modern” sites —while the rules were still being written — Colonial Williamsburg’s Black excavators were amassing the evidence on which we continue to build. By the time Historical Archaeology emerged as its own field of study, these men had recovered (and reconstructed) hundreds of buildings and collected thousands of artifacts.

Did they consider themselves archaeologists? It is hard to know. The earliest excavations in Williamsburg fell between the discovery of King Tut’s tomb in 1922 and news in 1939 that a Viking Ship had been found in the English countryside at Sutton Hoo. Notable archaeological discoveries must have seemed far from Tidewater Virginia. And yet patrons of a Duke of Gloucester Street garage were instructed to “Toot-an-Cum-In.” Did Linwood Williams consider himself an insider to that joke?

Although I hope he knew it, we acknowledge that he was. It has taken far too long to recognize that our discipline began with the work of Black excavators who were archaeologists. The names of some, we know already. Others, we still need to find. Perhaps they are on your family tree.

We do this work as we prepare for several anniversaries. In 2026, Colonial Williamsburg celebrates its centennial—one hundred years as a museum. It is no small thing to transform 300 acres of an 18th-century town, to restore 88 original structures and reconstruct another 500, to establish gardens, and then to bring those spaces alive with voices and movement and sounds.

Two years later, in 2028, Archaeology marks the hundredth anniversary of the first excavation on the site of the Capitol. Milestones have a way of making us reflective. As we stand at this one, we look back at where we have been, take stock of what we have become, and implement course corrections. It is time to recognize everyone who has played a role in building this extraordinary — but still unfinished — place.

Meredith Poole has been a Staff Archaeologists at Colonial Williamsburg for 35 years. Her career started with the 1985 excavation at Shields Tavern and has continued through more recent projects at Charlton’s Coffeehouse, the Public Armoury, and the Market House. Meredith has shared her enthusiasm for archaeology in a variety of forms: managing the Reconstruction Blog, leading archaeological walking tours along Duke of Gloucester Street, and overseeing the Kids Dig on Duke of Gloucester Street. She lives in Williamsburg with her husband, Joe. They have two adult children.

Resources

Noel Hume, Ivor “When Tut Went Phut; or, The Day Mr. Junior Changed His Mind” Colonial Williamsburg Journal, Spring 2002.

Colonial Williamsburg is the largest living history museum in the world. Witness history brought to life on the charming streets of the colonial capital and explore our newly expanded and updated Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, featuring the nation’s premier folk art collection, plus the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670–1840. Check out sales and special offers and our Official Colonial Williamsburg Hotels to plan your visit.