In 1766, Virginia’s lieutenant governor, Francis Fauquier, petitioned the Virginia House of Burgesses to construct a publicly funded hospital, the first of its kind exclusively dedicated to the treatment of people with mental illness. Eighteenth-century Virginians understood mental illness differently than we do today. For example, terms such as “a disordered mind” served as a catch-all diagnosis meant to describe any person thought to have a psychological disorder that rendered them incapable of intellectual reason. This included people who were experiencing a mental health crisis and those with cognitive disabilities. Previous generations of individuals whose peers viewed them as dangerous and disruptive due to their “disordered mind” had limited options. Those who were lucky might have had a relative or a friend able (and willing) to care for them. Those with less support could be confined at the local jail or might suffer chronic homelessness. Colonial Virginians intended for the hospital to serve as a safer space for people with mental illness; it was meant to better protect the community and the patients themselves. The Public Hospital was born out of a truly revolutionary idea for its time. Williamsburg’s Public Hospital (now Eastern State Hospital) admitted its first patients on October 12, 1773. The following timeline provides a reference for the history of Williamsburg’s Public Hospital.

The Public Hospital’s Creation

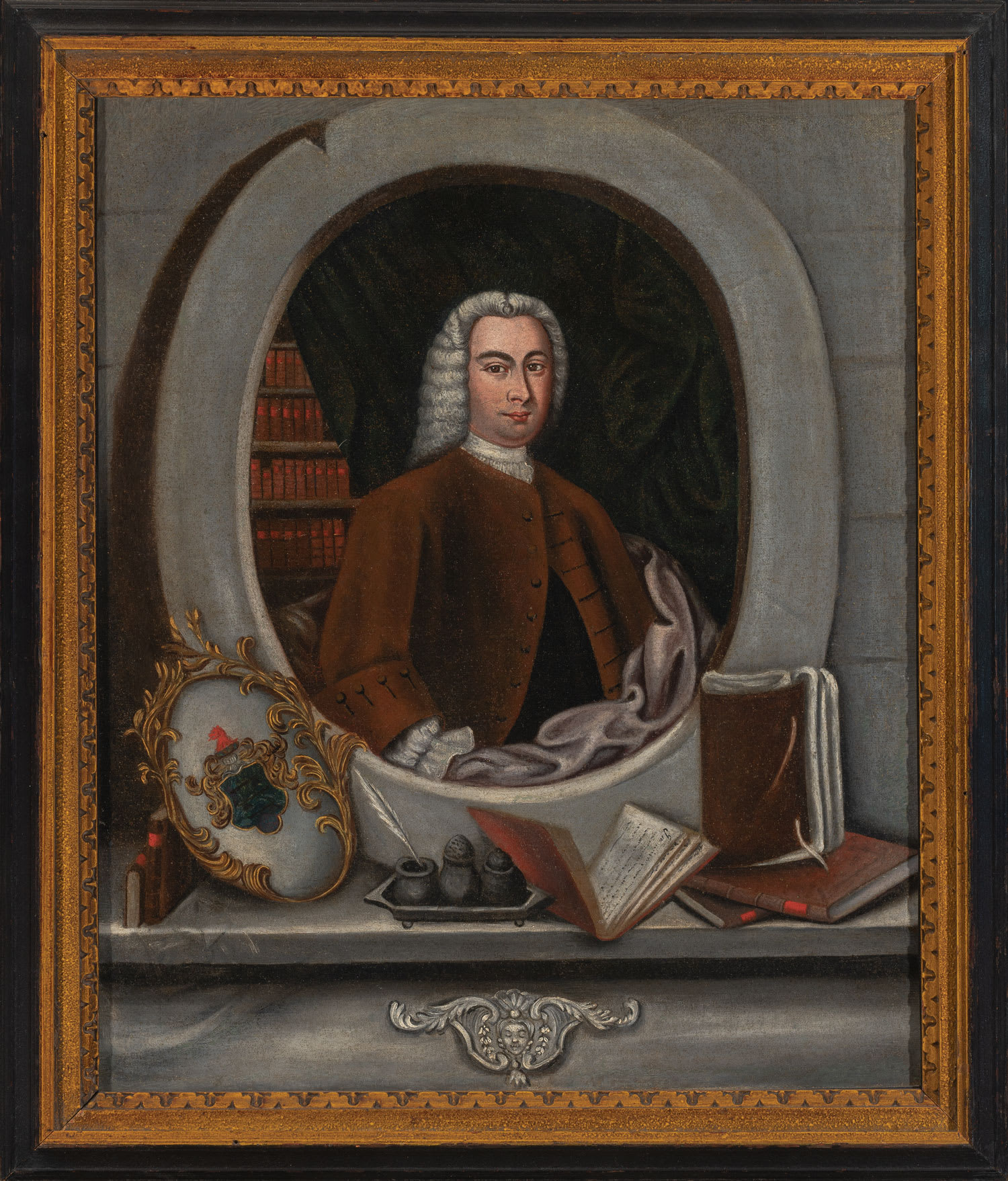

Inspired by the Enlightenment, Lieutenant Governor Francis Fauquier laid the groundwork for the first purpose-built mental health facility in British North America. Unfortunately, Fauquier was never able to see his project become a reality, as he died before legislation was passed for its creation in 1769.

November 6, 1766

Virginia’s lieutenant governor, Francis Fauquier, addressed the House of Burgesses, the lower house of the Virginia legislature, and advocated for a hospital for “People who are deprived of their Senses.” (By “senses,” Fauquier meant reason.)

July 6, 1769

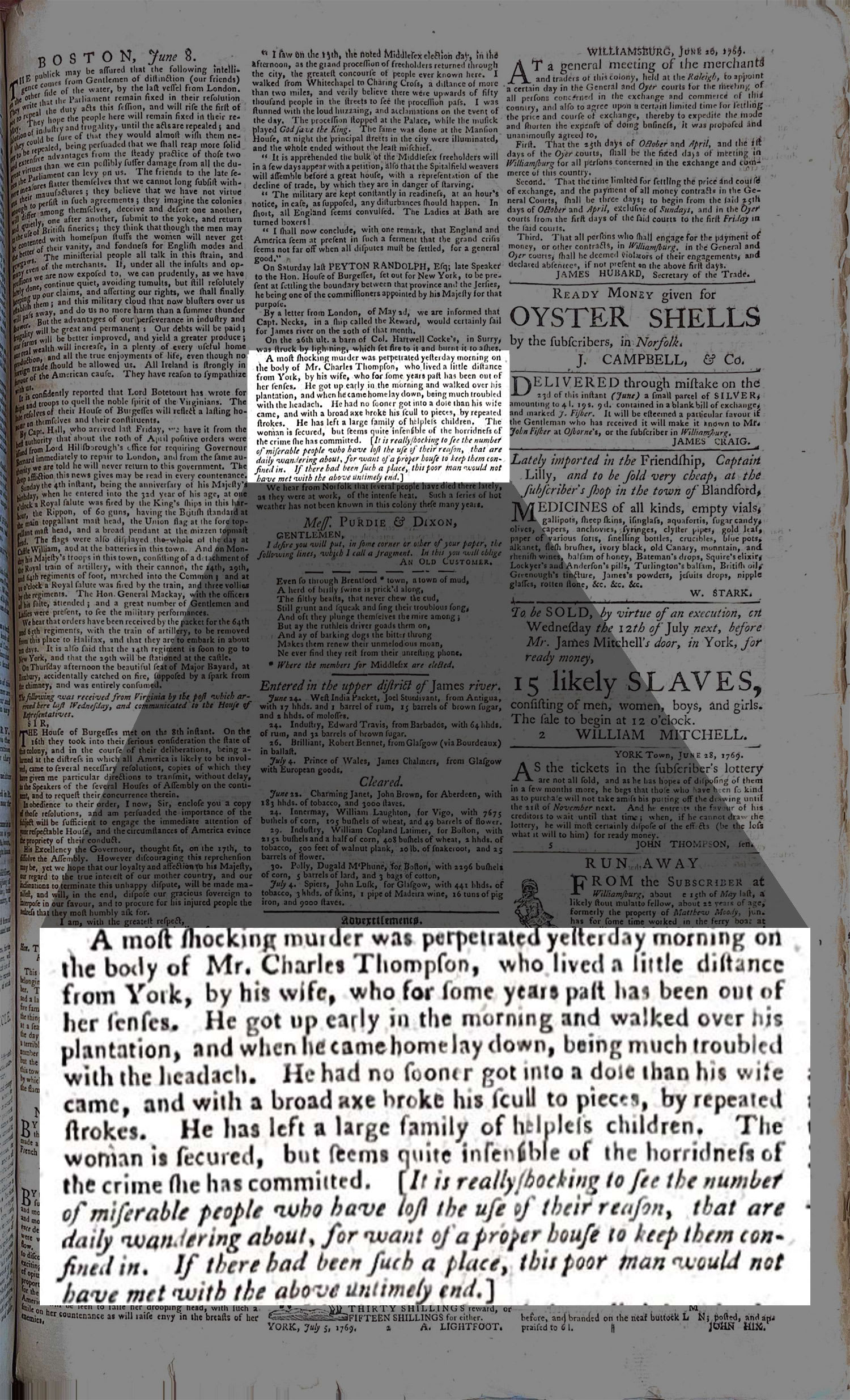

[Mrs.] Thompson murdered her husband, Charles Thompson, which shocked Williamsburg’s residents. Local newspapers raised concerns regarding the lack of options to care for those at risk of hurting themselves or others because of mental illness.

“It is really shocking to see the number of miserable people who have left the use of their reason, that are daily wondering about, for want of a proper house to keep them confined in. If there had been such a place, this poor man would not have met with the above untimely end.”

November 7, 1769

An Act to Make Provision for the Support and Maintenance of Ideots, Lunatics, and Other Persons of Unsound Minds layed out a framework for the building and management of the Public Hospital.

The language used to describe people with mental illness has changed significantly since the founding of the Public Hospital in the late eighteenth century. Although offensive today, terms like “ideot” and “lunatic” were appropriate medical and legal descriptions in the eyes of colonial Virginians.

The Public Hospital’s First Years

Once the Public Hospital opened, all legally free Virginians suffering from mental illness were eligible for admission. During the eighteenth century, enslaved individuals were not admitted to the hospital. James Galt was appointed keeper of the Public Hospital, while Mary Galt, his wife, served as the matron for the women. Dr. John de Sequeyra, was named the attending doctor at the Public Hospital and Dr. John M. Galt I also tended to patients.

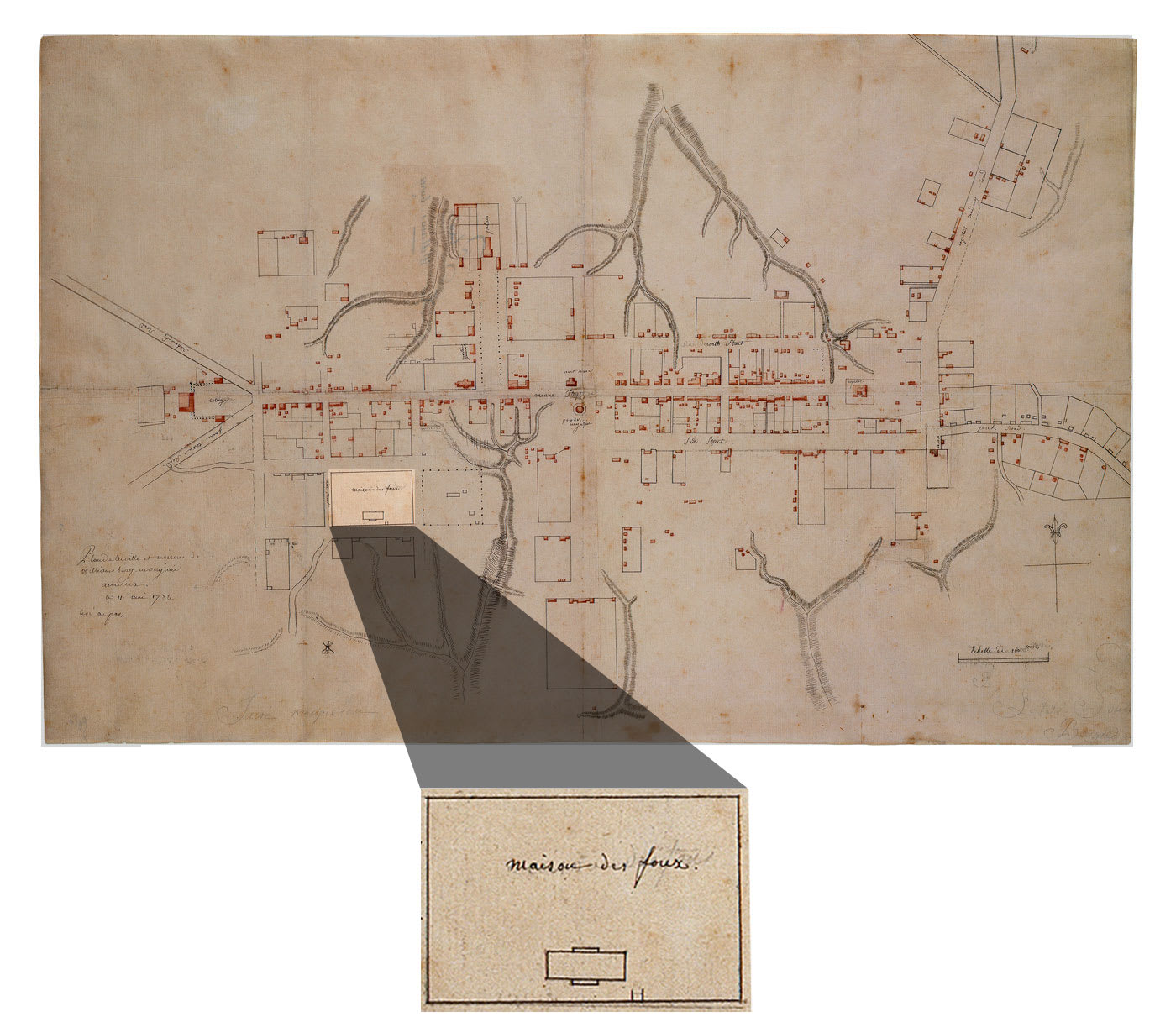

July 10, 1770

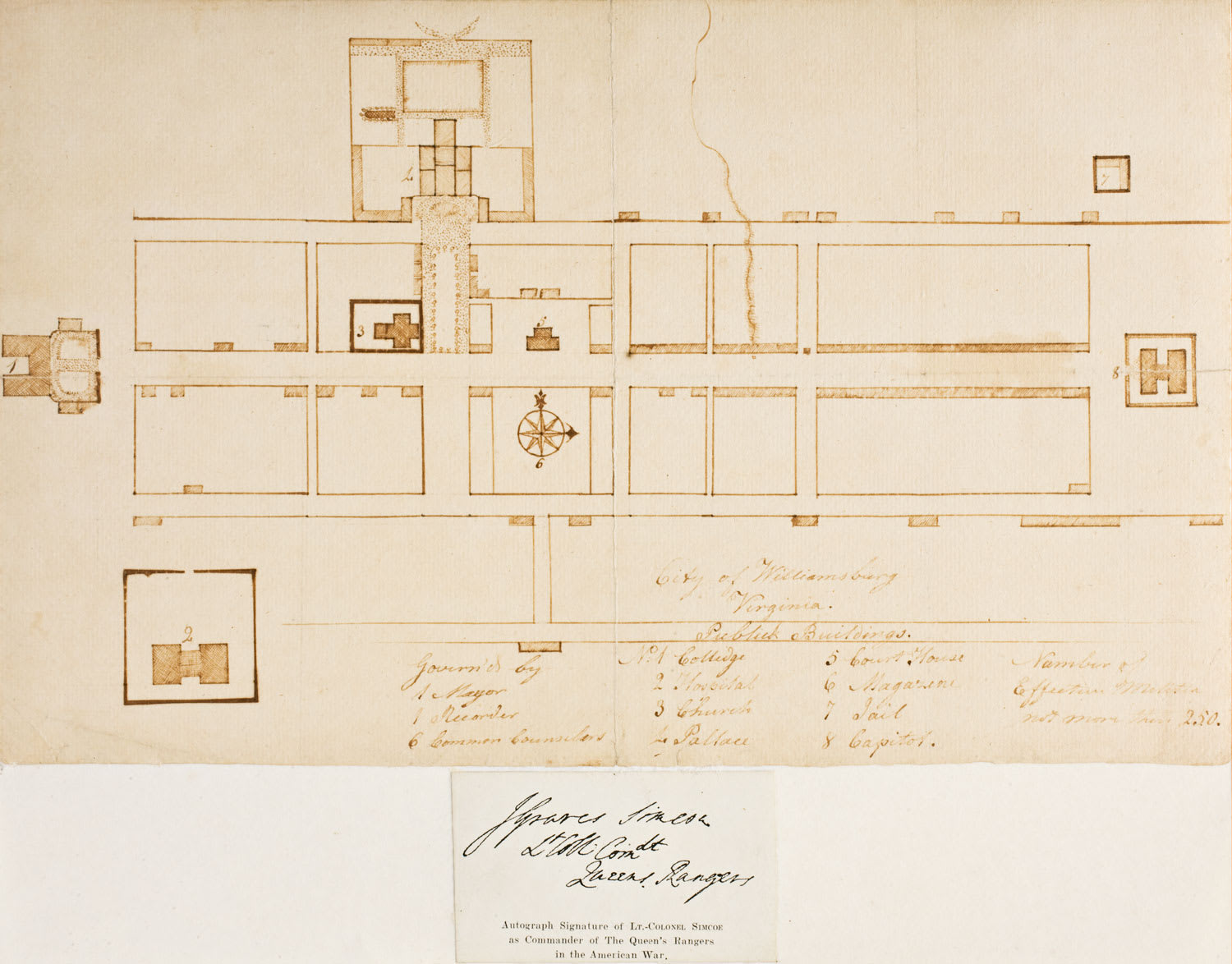

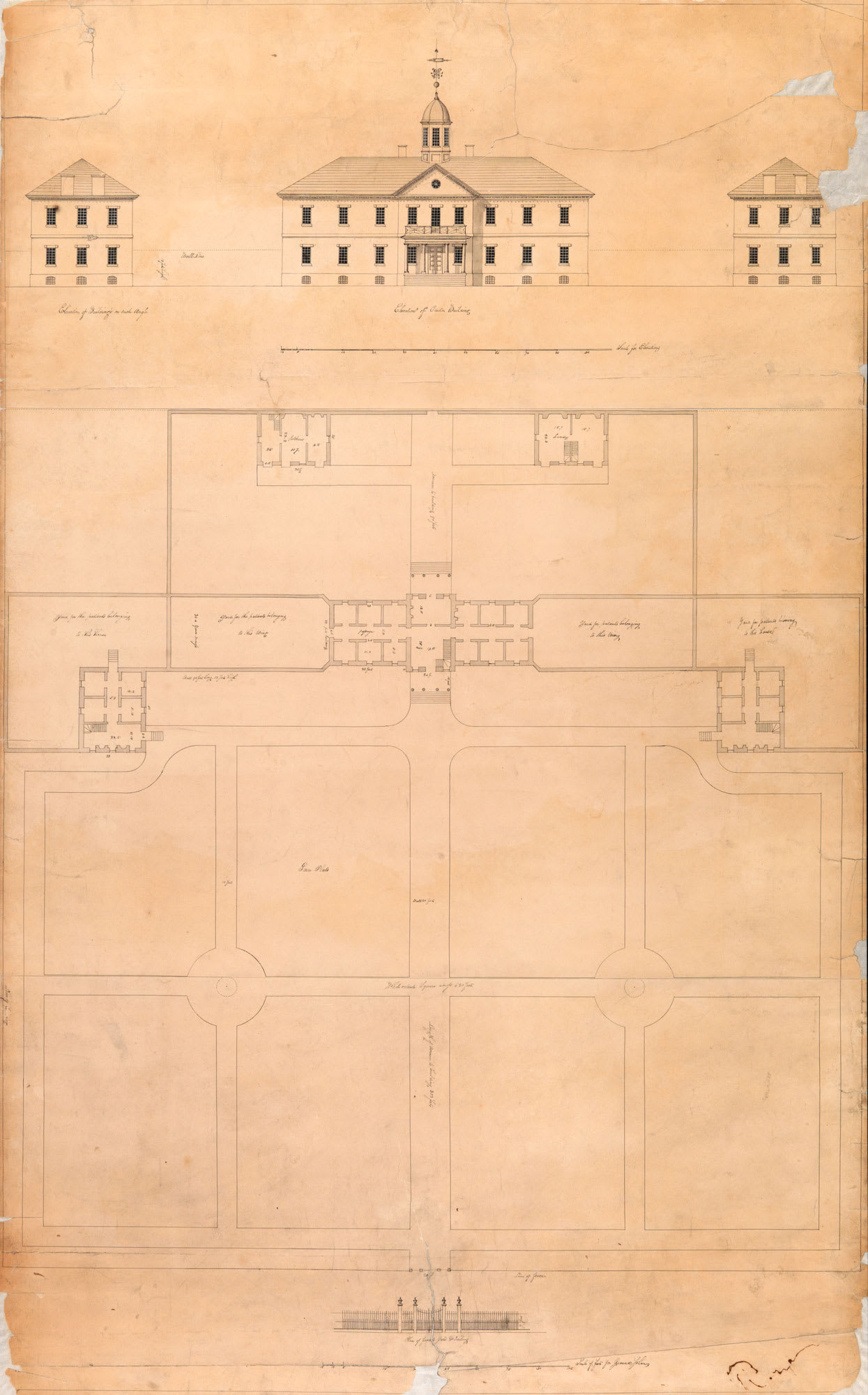

The hospital’s first appointed court of directors, drawn from Virginia’s gentry class, began planning its construction. They hired Robert Smith, an architect best known for his design of Carpenter’s Hall in Philadelphia, to design it.

January 1771

Williamsburg builder Benjamin Powell signed on as contractor and agreed to complete the building in two years for the sum of £1,070.

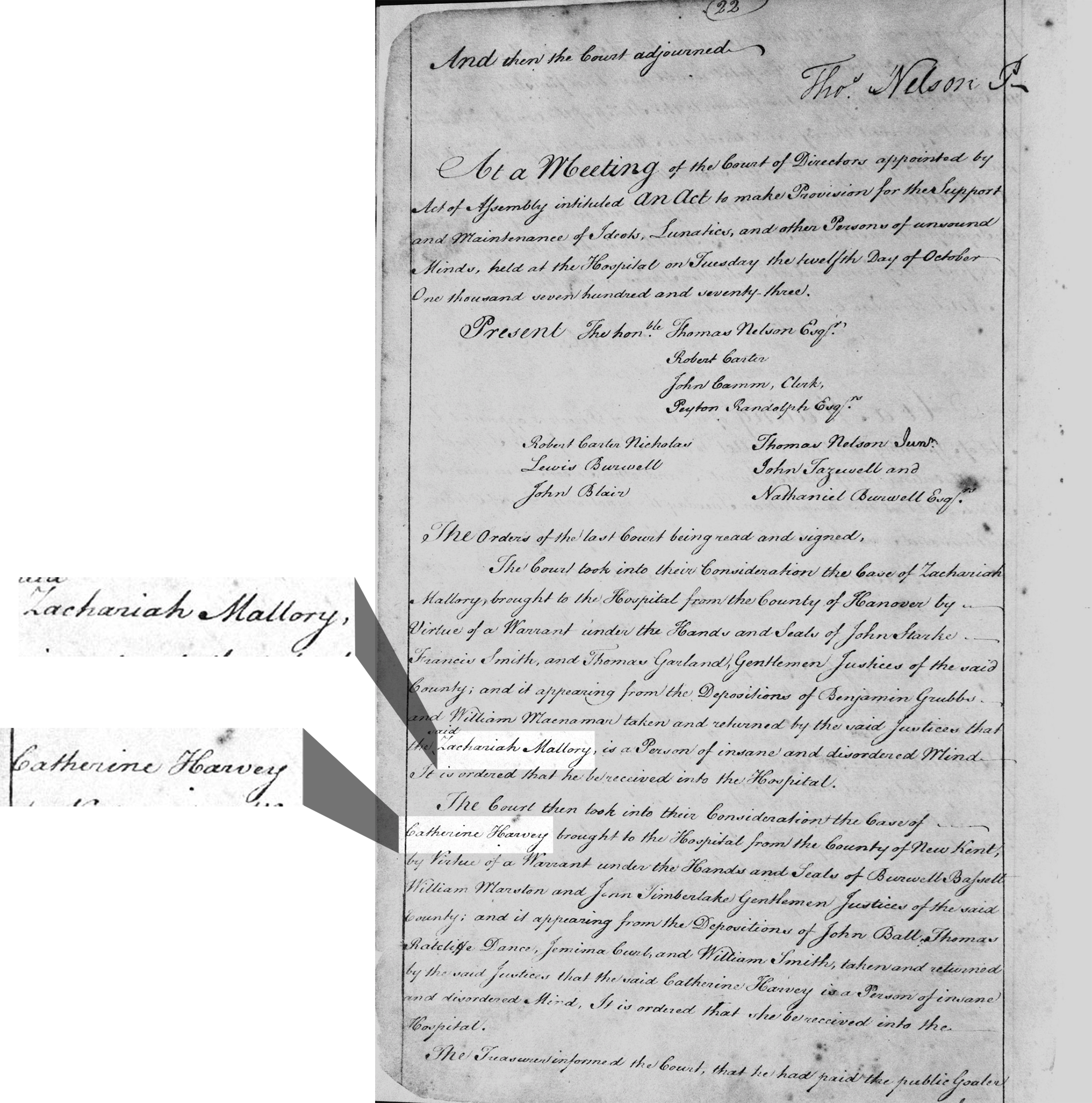

October 12, 1773

The Public Hospital accepted its first patients: Zachariah Mallory, who had previously been held at the county gaol (jail), and Catherine Harvey.

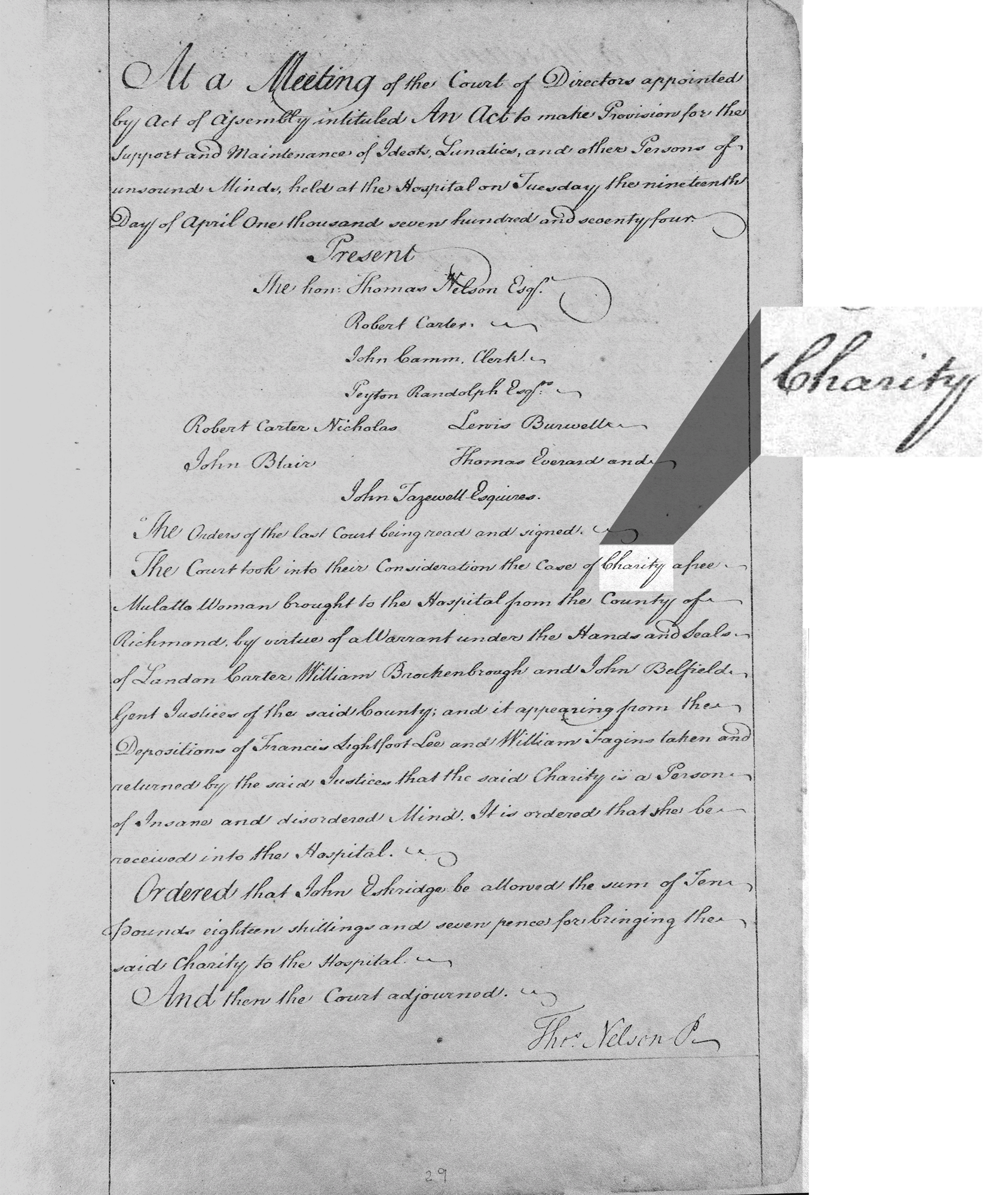

April 19, 1774

The Public Hospital accepted its first non-white patient: Charity, a free woman of mixed race.

The Public Hospital Experiences Disruptions

Records and primary source material regarding the Public Hospital during the late 1770s and early 1780s are sparse. "Efforts to keep the Hospital open and funded were somewhat successful during the American Revolutionary War, but we know little about day-to-day operations.

Fall 1782

The hospital was forced to close because of post-Revolutionary War inflation and a scarcity of provisions.

October 11, 1786

The court of directors announced that the Public Hospital’s building was in good repair and ready to accept patients. It reopened, James Galt resumed his role as keeper, and Dr. John de Sequeyra continued as the hospital’s physician.

1787

Due to insufficient Government funding, patients had to show they could pay for their care. Those with insufficient funds were turned away. This was a brief change in policy, and the Hospital went back to its "sliding scale" payment model in more prosperous times.

Ushering A New Era at the Public Hospital

The Williamsburg Public Hospital saw some changes in the 1790s, including legislation that imposed new requirements on treatment. After 1795, changes in staffing ushered in a new era for the Public Hospital.

December 1790

The Virginia legislature passed legislation that provided guidance on the administration of the Public Hospital. According to the 1790 Act, an attending doctor was expected to be onsite to treat patients at least once a week and the keeper of the hospital was expected to visit all patients in their cells every day.

1795

The Public Hospital’s attending physician John de Sequeyra died. He was replaced by John Minson Galt and Philip Barraud, local Williamsburg apothecaries. The court of directors endorsed the Virginia legislature’s 1790 requirements of care for the hospital’s patients.

1799

Philip Barraud left the Public Hospital.

1800

Dr. A. D. (Alexander Dickie) Galt, the son of John, was appointed the attending physician for the Public Hospital, where he remained until his death in 1841. Also in 1800, William Galt succeeded his cousin James Galt as keeper of the hospital.

Additional Resources

Onsite Experiences

Suggested Reading on the History of Mental Health in Early America

- Norman Dain, Disordered Minds: The First Century of Eastern State Hospital in Williamsburg, Va., 1766–1866 (Williamsburg, VA: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1971)

- Gerald N. Grob, Mental Institutions in America: Social Policy to 1875 (New York: Free Press, 1972)

- Mary Ann Jimenez, Changing Faces of Madness: Early American Attitudes and Treatment of the Insane (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1987)

- Roy Porter, Madness: A Brief History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002)

- David J. Rothman, The Discovery of the Asylum: Social Order and Disorder in the New Republic (Boston: Little, Brown, 1971)

- Sarah L. Swedberg, Liberty and Insanity in the Age of the American Revolution (New York: Lexington Books, 2021)

- Shomer S. Zwelling, Question for a Cure: The Public Hospital in Williamsburg, Virginia, 1773–1885 (Williamsburg, VA: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1985)