With the expansion of the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, new galleries provide exciting possibilities for new exhibitions. A bold and dramatic new arrangement features several architectural fragments displayed on the high walls of the skylit Pamela J. and James D. Penny Court, in the heart of the Dewitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum.

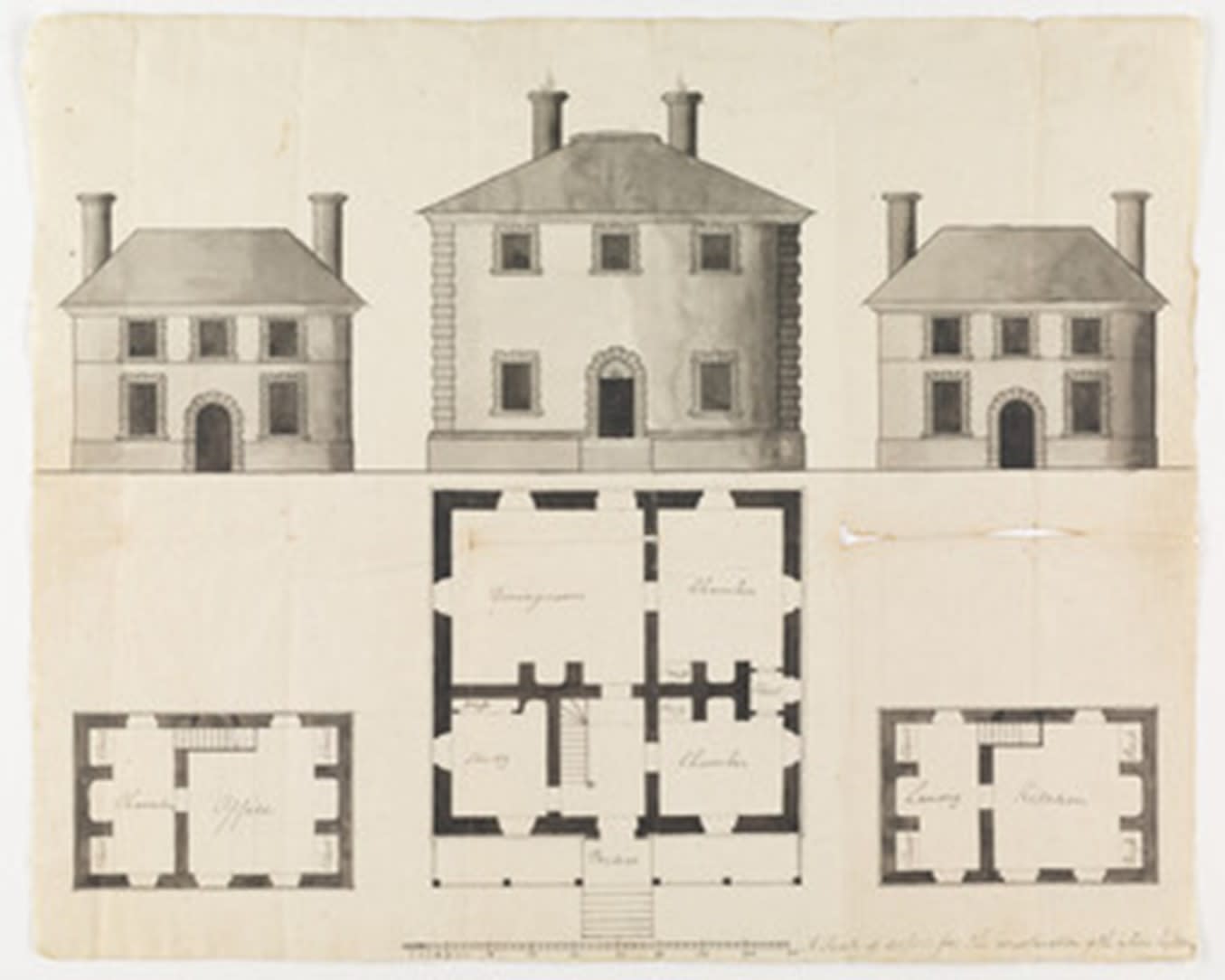

Colonial Williamsburg has the privilege of exhibiting a rare 18th-century stairway on loan from the historic house Menokin, near Warsaw, Richmond County in Virginia’s Northern Neck. Menokin was built for Francis Lightfoot Lee and his bride Rebecca Tayloe of nearby Mount Airy at the time of their marriage in 1769 (seen in the drawing below). Menokin is remarkable perhaps as much for its association with Declaration of Independence signer Francis Lightfoot Lee as it is for its locally quarried rare brown ferruginous sandstone (erroneously called ‘Choptank Sandstone’) and surviving architectural interiors. By 1968, after several successive owners and vacancies, the house had fallen into disrepair. The interior woodwork was removed to a storage facility, and in the 1980s it was transferred to the care of the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities. The stair represents a brilliant single example of vernacular American architectural features in the last third of the 18th century.

Author and historian Camille Wells has described the overall design and construction of Menokin as having a “call-and-response relationship with Mount Airy,” that ultimately reflects as much of the complicated patriarchal imprint of John Tayloe II as it does the ownership and management of son-in-law Francis Lee. In marrying Rebecca Tayloe, Lee had transferred his estate from his inherited Loudoun County to Richmond County. The implicit bargain was for Lee to gain the 1,000-acre Menokin tract and a new house to be built. Construction of the house and multiple associated estate structures was started in 1769 at the time of the Lee-Tayloe marriage. By 1771, the young Lees had moved to the property but resided in a “modest secondary dwelling.” However, it has been suggested that partly because of Tayloe’s patriarchical influence, Lee, as construction manager, had delayed and meddled in the actual construction details and schedule. The interiors of the house, including the staircase, which bears similarities with the design and construction of nearby Grove Mount on Rappahannock Creek (now Cat Creek), built between 1782 and 1787, may not have been completed until between 1780-90.

Stairways are unique expressions of style, function, and construction problem-solving as their builders had to conform to the space and physical framework within the house. This stair is no exception. Its boldly molded handrail with swept curve, generously proportioned raised panel wainscoting, wrought nails, pinned mortise and tenon joinery, double S-curved brackets, and early paint history confirm it as the first period stairway in the house. There are vernacular aspects reflected unique to this house as well.

First and foremost is the fact that the stair passage is relatively small for a grand stone house and only a winding stair construction could provide the access to the second floor. Secondly, there are some other features that reflect a vernacular style unique to this house. The balusters are diamond-oriented but otherwise slender straight one-inch sticks of yellow poplar, crowded four to a tread unlike the more common robust three per tread in most Virginia houses of this scale. A similar staircase baluster treatment can be seen at Brice House, Annapolis, Maryland. One plausible explanation for the unusual thin square balusters is the emerging style of iron balusters in British stone stairways of the time. Also unusual is the original white paint under the surviving early brown, as found from sampling and paint analysis (below).

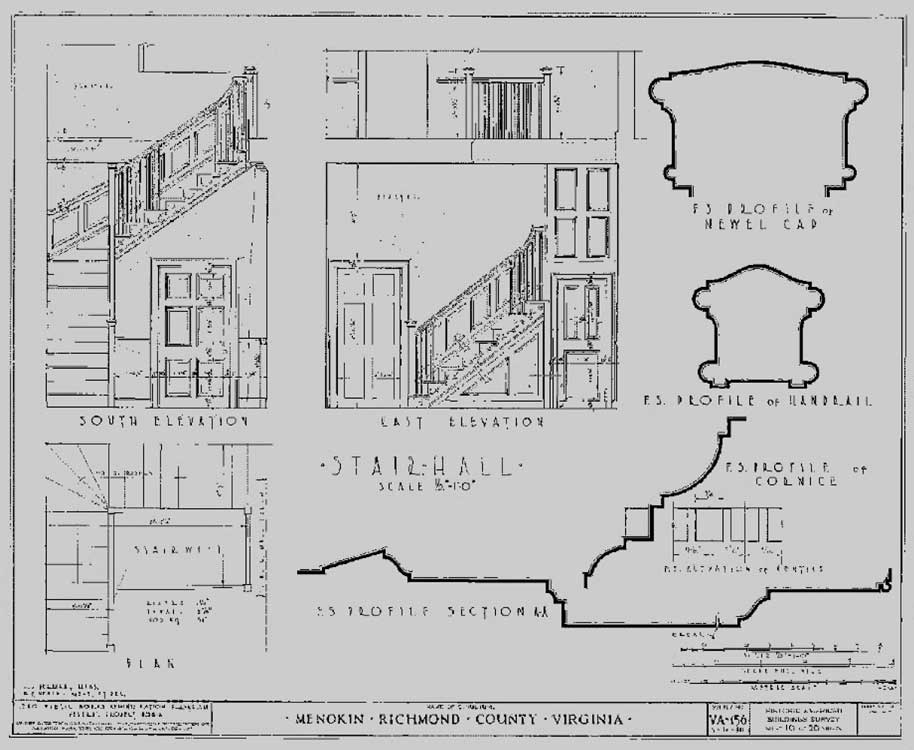

The treads are relatively thin at three-quarters of an inch. Risers and triangular fills below the wall-raised panel were unpainted yellow pine, as seen in the 1940s Historic American Building Survey (HABS), National Park Service photographs. These are elements that may reflect a local builder’s capacity and experience as much as the dominant aristocratic architectural style of the day.

There is no doubt that the main passage winding stairway was the first one built in the house. The better part of the first flight was selected for exhibition in Williamsburg. If identifying and extracting the surviving collection of separated and disjoined architectural elements from storage was not challenging enough, reconstructing them for exhibit on a high gallery wall certainly will be a monumental challenge. This has been the focus of a team of museum professionals over the last several months.

Conservation of the stairway was carried out in the Wood Artifacts Lab. Without the obvious house framing, perhaps the greatest challenge was determining its proper configuration. This was somewhat like completing a jigsaw puzzle with only half of the pieces. Since the passageway framing in the house was lost in previous partial collapse, the removed stairway can only be reassembled based on its own physical evidence. For example, the raised panels clearly measure a 40-degree slope that would necessarily match the angle of the railing. Fortunately, we have the 1940's drawings and photographs by HABS (below).

The surviving elements feature the stair brackets, several treads, the ground floor newel post, a majority of the diamond-profile balusters still attached to the railing with swept-end, a sawn-off fragment of the outer stringer still pinned to the bottom of the newel, the lower triangular raised panel, and the wall raised panel (below). All the other elements required for installation in the gallery had to be fabricated in the lab.

A design was selected to minimize overall weight while conveying the essence of the three-dimensional construction. In addition to shortening the custom-made new tread widths to 12 inches, all of the new parts were built with a no-spare weight tolerance. For example, the shortened treads were cut to give the illusion of full three-quarter-inch thickness around all edges but reduced in thickness in the center to a mere eighth of an inch. Likewise, half-inch medium density overlay (MDO) plywood stringers hold one-eighth-inch thin Baltic Birch plywood risers with a faux-grain-painted pine pattern to mimic the original boards. The new 12-foot-high upper newel post is constructed as a boxed beam with half-inch plywood MDO plywood, with a removable extension to make the full 12 feet of height. The new elements feature a painted and faux-aged treatment for the overall integration of the display. The design and missing parts were custom made by a talented team of conservators and interns, and later will be mounted by the team of art handlers and mount makers.

The conservation treatment featured a minimally invasive and stabilizing aspect for future protection. Original mortises in the newel now hold the tenoned ends of the new supportive stringer board. These joints are held with pins like the original construction. Broken tenons on the handrail were repaired with reversible hide glue barriers and bulked epoxy and wood fills. The new tenons are only pinned in the mortises and not glued. The new elements were locally drilled out as much as possible to allow for the projecting old nails of adjacent old members. Only a minimum of screws were added to hold the old elements in place on the new added boards — from the front when they would imitate conspicuous large nails originally, or from the back when the original front nailing was small and covered with paint. Selectively applied small 23guage pneumatic pin nails enabled consolidation of loose balusters, as you can see below.

The lead-based brown paint was in unstable condition having deteriorated significantly in its old age. The surface was somewhat chalky — almost white in places — and quite fragile. The paint was consolidated with a very thin coating of a high-grade acrylic resin solution to ensure safety when handling and dusting. This also diminished the chalky appearance by re-saturating the brown color.

We’re looking forward to updating you on the installation of this fascinating stairway at the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg in early 2021.

Christopher M. Swan has worked as an intern and now Sr. Furniture Conservator at Colonial Williamsburg since 1994. He enjoys playing music out loud in his spare time.

Resources

- Vernacular Domestic Architecture in Eighteenth-Century Virginia

- Classic Commonwealth: Virginia Architecture from the Colonial Era to 1940

- Measuring buildings for the Historic American Buildings Survey

- Mark R. Wenger on the Evolution of the Virginia center passage

- “Dower Play / Power Play: Menokin and the Ordeal of Elite House Building in Colonial Virginia,”

- Rabble with a Cause- W&M Geology at Menokin, by Chuck Bailey

Colonial Williamsburg is the largest living history museum in the world. Witness history brought to life on the charming streets of the colonial capital and explore our newly expanded and updated Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, featuring the nation’s premier folk art collection, plus the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670–1840. Check out sales and special offers and our Official Colonial Williamsburg Hotels to plan your visit.