With the Ratification of the United States Constitution in 1788, America had a new framework of government that endeavored to fix the deficiencies of the previous Articles of Confederation. Five years after the Treaty of Paris secured its Independence, the United States was still struggling to discover a way for 13 diverse and sovereign nations to work together for a greater goal.

Under the previous system, delegates for the Continental Congress were appointed from the state’s provincial legislatures, each with their own unique systems of government. Under Article I of this new Constitution, the people would have the first opportunity in the history of their young nation to have a direct say in who would represent them. The lower house of Congress, the house of representatives would be comprised of representatives directly elected by those eligible to vote while the upper house, the Senate, would be appointed by the states. With the election of George Washington as president viewed by nearly everyone as a fait accompli, the race as to who would represent Americans in their first Congressional session became the focus in this new epoch of American Democracy.

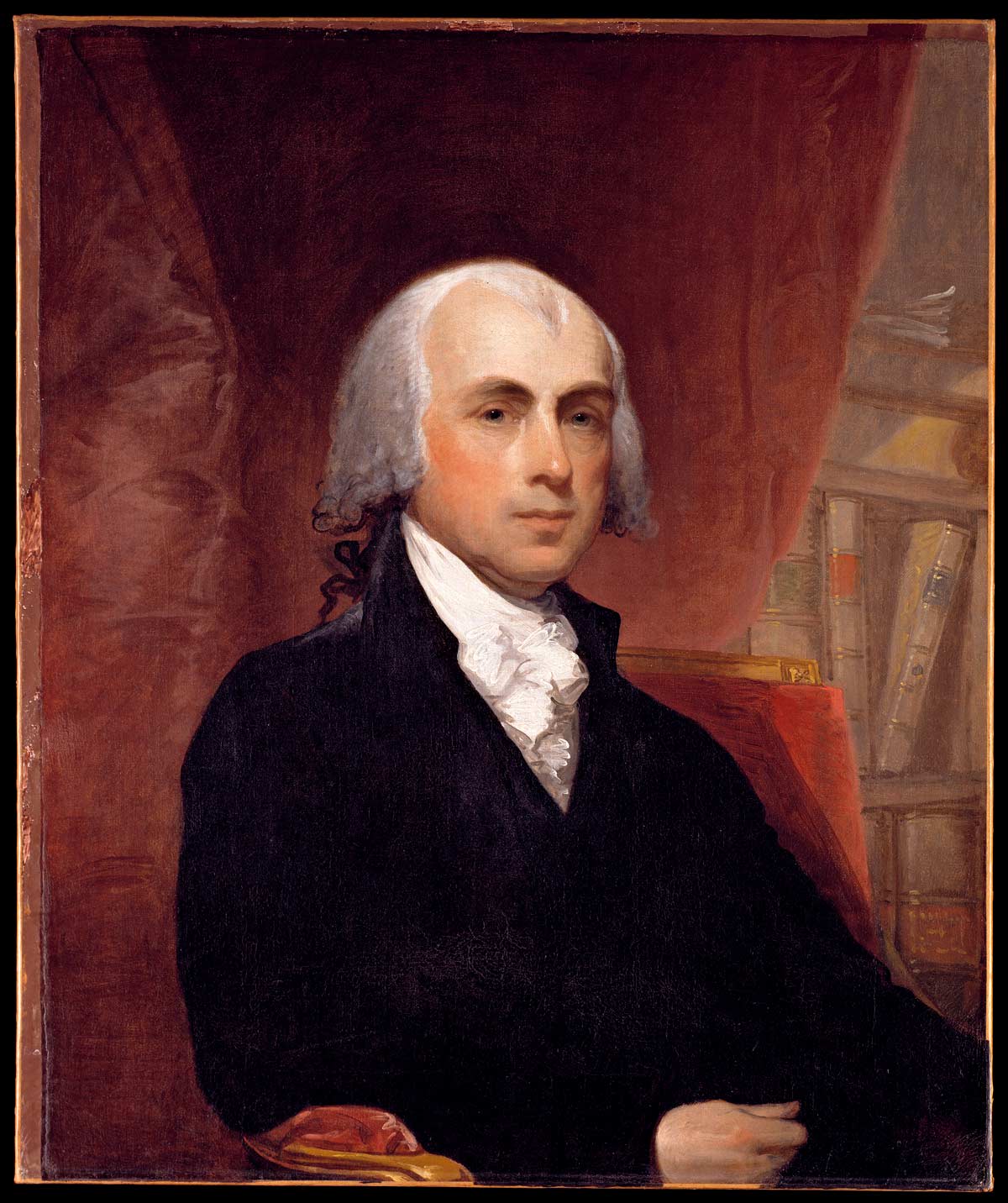

For men like James Madison, historically proclaimed ‘Father of the Constitution’, his place amongst this new Federal Government seemed almost certain. In reality, the trial of the election season of 1789 was anything but. Madison was never the most popular amongst the common man. In 1777, he famously lost his bid for reelection for the General Assembly of Virginia after refusing to treat the freeholders of his county seat to rum, whiskey and other libations, instead losing his seat to Charles Porter, a tavern keeper in Orange County Virginia. (Learn more about this common practice, called treating, in a recent blog post, here.)

Moreover, his public actions in defense of a stronger system of government and the separation of church and state had earned him a list of legendary political rivals like Patrick Henry and George Mason. Henry was not only a dynamic orator and man of the people, he was also a capable politician on the state level. When the time came for the General Assembly to appoint the two statesmen to represent Virginia in the new US Senate, Henry insured Madison’s name would not be one of those considered.

Henry did not stop there. It would fall to the General Assembly to also draw the Congressional district lines for Virginia’s representatives, the lines were drawn in such a way to ensure Madison would have an uphill climb for a chance to represent Virginia in this new Congress; he would have to run against a friend, a rival and a man whose popularity in the Old Dominion equaled and in some ways exceeded Madison’s: James Monroe.

Monroe was a hero of the Revolution. A veteran, who still carried the musket ball from the battle of Trenton in his shoulder, Monroe was held in high regard for his honesty and integrity. The two had landed on opposing sides of the Ratification debate, Monroe believing the Constitution still needed several necessary amendments before it could fully earn his trust. In those debates, Madison succeeded narrowly with the promise that, once ratified, he would champion a Bill of Rights with a series of amendments submitted to the new congress. With Monroe as his opponent, his seat in Congress wasn’t the only thing on the line. Madison risked being unable to fulfill those aforementioned promises.

The two set out together in the brutal winter of 1789. Though they campaigned against one another, they remained each other’s near constant travel companions as they travelled from place to place throughout their district. They paid for musicians to entertain a small Lutheran congregation and they made stump speeches to wind-chilled crowds.

One anecdote from Paul Jennings, Madison’s enslaved manservant, is quite telling. Jennings, who provided an incredible amount of insight into Madison’s life, (seriously, his extraordinary life deserves a blog post all his own) eventually wrote a memoir A Colored Man's Reminiscences of James Madison, tells a humorous story of a failed attempt by Madison to curry favor with some of the local population:

“Mr. Madison was anxious to be elected, and sent his chariot to bring up a Scotchman to the polls, who lived in the neighborhood. But when brought up, he cried out: "Put me down for Colonel Monroe, for he was the first man that took me by the hand in this country.”…”His friends joked Mr. Madison pretty hard about his Scotch friend, and I have heard Mr. Madison and Colonel Monroe have many a hearty laugh over the subject, for years after.”

While traveling to Louisa County through a winter storm, the winds grew so cold Madison actually lost a small chunk of his nose due to frostbite. Despite that, the campaigning went in Madison’s favor. He won the election by the tip of his nose (pun very much intended.)

This slight loss of appendage is small compared to what America could have lost, our Bill of Rights. On entering Congress, Madison was true to his word. The first ten amendments to our Constitution were ratified in December of 1791. Though they often found themselves on the opposite sides of the aisle, Madison and Monroe remained life-long friends and, in some of their greatest crucibles, were essential to one another’s success.

America’s electoral system has always been fraught with conflict, party, and high stakes; it could be said those various qualities are as natural to democracy so long as people’s opinions are diverse. However, in the election cycle of 1789 two famous Virginians provided an example that so long as we fight issues and not people, the American people can always remain members of the same family.

Bryan Austin is a professional actor, writer, and interpreter with over 20 years in the theatre and museum world. His presentations as Madison have taken him to schools and audiences across the country along with interviews and articles with TIME and various other local newspapers.

Colonial Williamsburg is the largest living history museum in the world. Witness history brought to life on the charming streets of the colonial capital, plus, explore our newly expanded and updated Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg featuring the nation’s premier folk art collection, plus the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670–1840. Check out sales and special offers to plan your visit.