When we think about mental illness, what words do we use?

Those of us familiar with modern mental healthcare are likely used to the chemical language of neurotransmitters. Your friend jokes that a TV show they love is their main source of serotonin. A news article about social media focuses on how an app might affect your dopamine receptors. Today, we accept that we can understand our physical brains – our minds – through the chemistry of the nervous system, and when we start to feel illness developing there, we often look to neurochemistry to help fix it. A selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) may not be a total cure for someone’s struggle with depression, but they might hope that increasing the serotonin levels in their brain will improve their energy enough to tackle getting out of bed.

Looking back to the 1770s, it’s easy to recoil at how different the physical side of mental health treatment seems. Rather than familiar, modern medication, strange practices like bloodletting and digestive purging appear in Public Hospital records as well as in dramatic fiction. On the surface, those may seem harmful – so what did they have to do with fixing the brain? Part of the answer lies in how the British medical world conceptualized the body. Psychology and neurology were still disciplines largely belonging to philosophers who speculated on how the mind and body were connected. These same philosophers were ultimately missing the technology to delve deeper into cells and their chemicals, but – as humans do – they still sought explanations within. When it came to the body, the ancient Greek doctor Galen’s “four humors” theory was all but dead, largely disproven by William Harvey’s 17th-century discovery of blood circulation. A language of physics began to dominate the medical field, specifically in relation to how fluids were moving around the body and pushing against their vessels.

Students of Dr. Herman Boerhaave - one of the most prominent early-18th-century medical thinkers - learned that to be sick was to be in a state of obstruction, stagnation, non-movement. The “solids” or “fibers” of the body (vessels, muscles, organs) could be too rigid or too loose; the fluids (or “humors”) could be too thick or too thin, too slow-moving or too fast. When those conditions caused symptoms of illness, they could be treated by fixing the stagnation and getting the fluids flowing again.

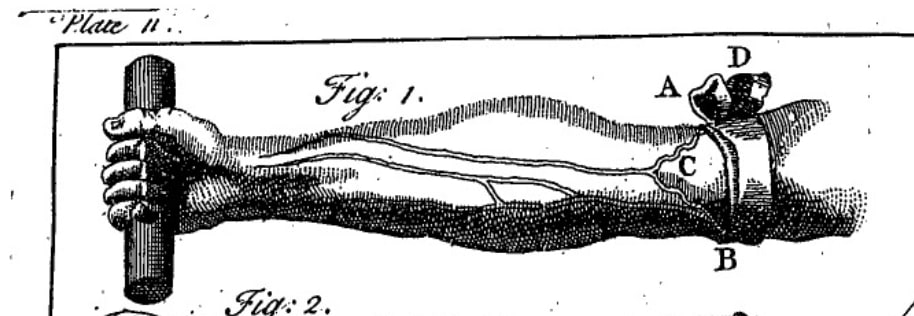

The 18th century medical world was especially concerned with how blood circulated, because they observed that whenever blood appeared to get thick, travel too fast, or get into places it shouldn’t, it caused inflammation. That hot, pulsing headache that feels like something’s stuck in your head? To an 18th-century medical professional, that inflammation could be a reason to try and thin out your blood or draw it elsewhere in the body. (For some symptoms, a doctor might suggest creating a blister on the back of your neck – when it broke and fluid seeped out, that motion might have vacuumed the stagnant blood particles away from your head!)

Just like it did for physical conditions, medicine tried to explain much of mental illness using the motion and obstruction of the blood as well as the inflammation it caused. Digestive problems could turn crude bits of food into irregular, thick blood that might find its way upwards and clog the brain area. A weak brain structure could fail to adequately push blood through its vessels. Intense study or emotions - mental overexertion - could pull blood up towards the brain where it might then sit stagnant. Anger could speed up the circulation. There were many reasons why someone might have found themselves experiencing altered thought patterns or clouded reason, but with medicine’s focus on fluid motion, the treatment for mental illness often mirrored treatment for other inflammatory diseases.

This is where bloodletting, purging, blistering, and other physical remedies came in. The aim was often to calm inflammation or nervous irritation and promote the flow of fluids like urine, sweat, and saliva, ultimately hoping to restore good blood circulation and ‘unlock’ a mind whose reason had been clouded by those bodily symptoms. Whether someone was suffering the sluggish, flatulent anxiety of melancholy or the heated agitation of mania, keeping the body ‘open’ by circulating fluids was a common physical goal. It’s not exactly the neurochemistry with which we’re familiar today, but this body-focused mental health treatment followed standards of medicine that were commonly accepted among the 18th-century British public.

However, just like our modern discussions about psychiatric medication, bleeding and purging weren’t the end of the mental health conversation. Doctors recommended lifestyle changes like exercise, fresh air, calm environments, talking to friends, or finding ways to regulate your emotions – a total care regimen for mental illness might include a purge, sure, but it’s likely to have also involved practical elements not too dissimilar from what you might encounter in your own life, today.

These more familiar remedies are often overshadowed in history by the treatments that seem totally alien. The 19th century, as it developed new techniques in psychology, looked back with disdain on the 18th-century purgative therapies; so, then, did the 20th century condemn its predecessor for its lack of neurochemical understanding. Even now, we haven’t figured out a singular cure-all. As many with mental illness know, mental health care today relies on a diverse assortment of therapies, medications, and other support, to help work through thought patterns and emotions.

It’s much easier to discard the horrors of yesterday than it is to investigate them. As we continue to open meaningful conversations around mental health and its history, pay attention to those words that might sound strange (like bloodletting, perhaps.) Ask “why” whenever possible. Even though theories about mental health look different, chances are, people of the past were tackling the same questions about emotions, relationships, and care as we are today.

Resources

- William Cullen, First Lines of the Practice of Physic, vol. 1 (Massachusetts: 1790), 19-38.

- Robert James, A Medicinal Dictionary (1743-45), see entries for “Mania” and “Melancholy”.

- David Macbride, A Methodical Introduction to the Theory and Practice of Physic (Edinburgh: 1772).

- L.J. Rather, Mind and Body in Eighteenth Century Medicine (California: University of California Press, 1965).

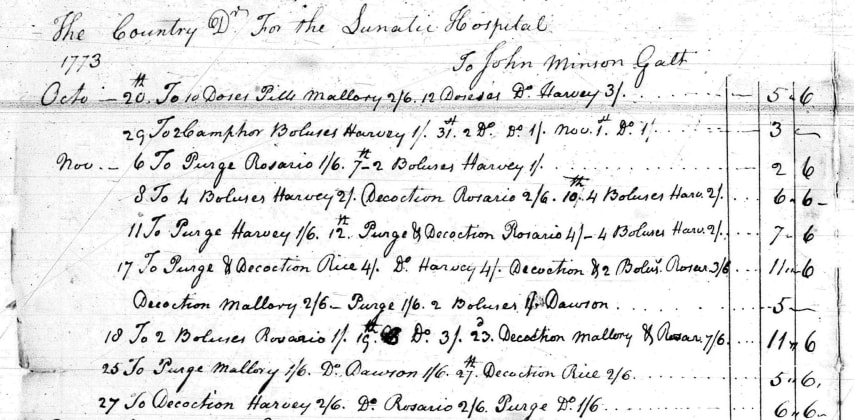

- The Country Dr. for the Lunatic Hospital to John Minson Galt, 1775, invoice, from the Brock Collection, box XL, Huntington Library (accessed April 4, 2023).

- Herman Boerhaave, Boerhaave’s Aphorisms: Concerning the Knowledge and Cure of Diseases (London: 1776).

- Richard Brookes, The General Practice of Physic, vol. 2, 5th ed. (London: 1765).

Colonial Williamsburg is the largest living history museum in the world. Witness history brought to life on the charming streets of the colonial capital and explore our Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, featuring the nation’s premier folk art collection, plus the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670–1840. Check out sales and special offers and our Official Colonial Williamsburg Hotels to plan your visit.