Their shadows fall across excavated foundations and their discarded photographic plates are visible on sawhorses, yet their faces and stories are relatively unknown. The photographers of Williamsburg’s restoration were an invisible yet critical part of the team. Photography played a crucial role in the initial decade of restoration of Virginia’s colonial capital. Dr. W.A.R. Goodwin used historical photos, along with a tour of the town in 1926, to stimulate John D. Rockefeller Jr.’s interest in restoring Williamsburg to its 18th-century appearance.

In 1927, shortly after Rockefeller selected the Boston architectural firm of Perry, Shaw & Hepburn to undertake the task, the architects’ Williamsburg office began supplementing Goodwin’s sets of photographs with copies of late 19th- and early 20th-century views of Williamsburg which they collected from town residents and located at other repositories. They used these early photographs to assemble clues about the original location and appearance of buildings no longer standing or extant only as ruins. Photographs became a key element in the process of recreating the 18th-century town, along with maps, manuscripts, archaeological excavations, and existing architectural evidence. As the work progressed, Perry, Shaw & Hepburn authorized the creation of a large body of photographs documenting each stage of the restoration for every building. Their emphasis on the photographic medium as one of the tools essential to restoration work established an important precedent for the movement in America.

Pre-restoration era photographs formed the nucleus of the collection assembled by the architectural team in the late 1920s and 1930s. Through the assistance of town residents and amateur photographers, the research staff gathered as many images as they could of extant historic structures in Williamsburg. These provided critical evidence for making decisions about how to proceed with work at each site. Mr. Clyde Holmes, a Williamsburg resident who collected news clippings and photographed Williamsburg buildings to aid Dr. Goodwin’s early efforts to interest someone in funding the restoration, contributed over 2,000 images of street scenes and neighborhoods.

Perry, Shaw, & Hepburn also asked contractors Todd and Brown Inc., hired in 1928, to conduct a photographic survey. They methodically recorded each structure on each block, whether 18th, 19th, or 20th century, to document the current town layout. Careful study of these helped with planning the complex process of demolishing, moving, reconstructing, or restoring buildings.

Several professional photographers joined the team on a contract basis to document the progress of the restoration work. Thomas Layton of The Layton Studio at 507 E. Broad Street, Richmond, Virginia photographed archaeological excavations and early stages of reconstruction or restoration at sites from 1928 until 1930.

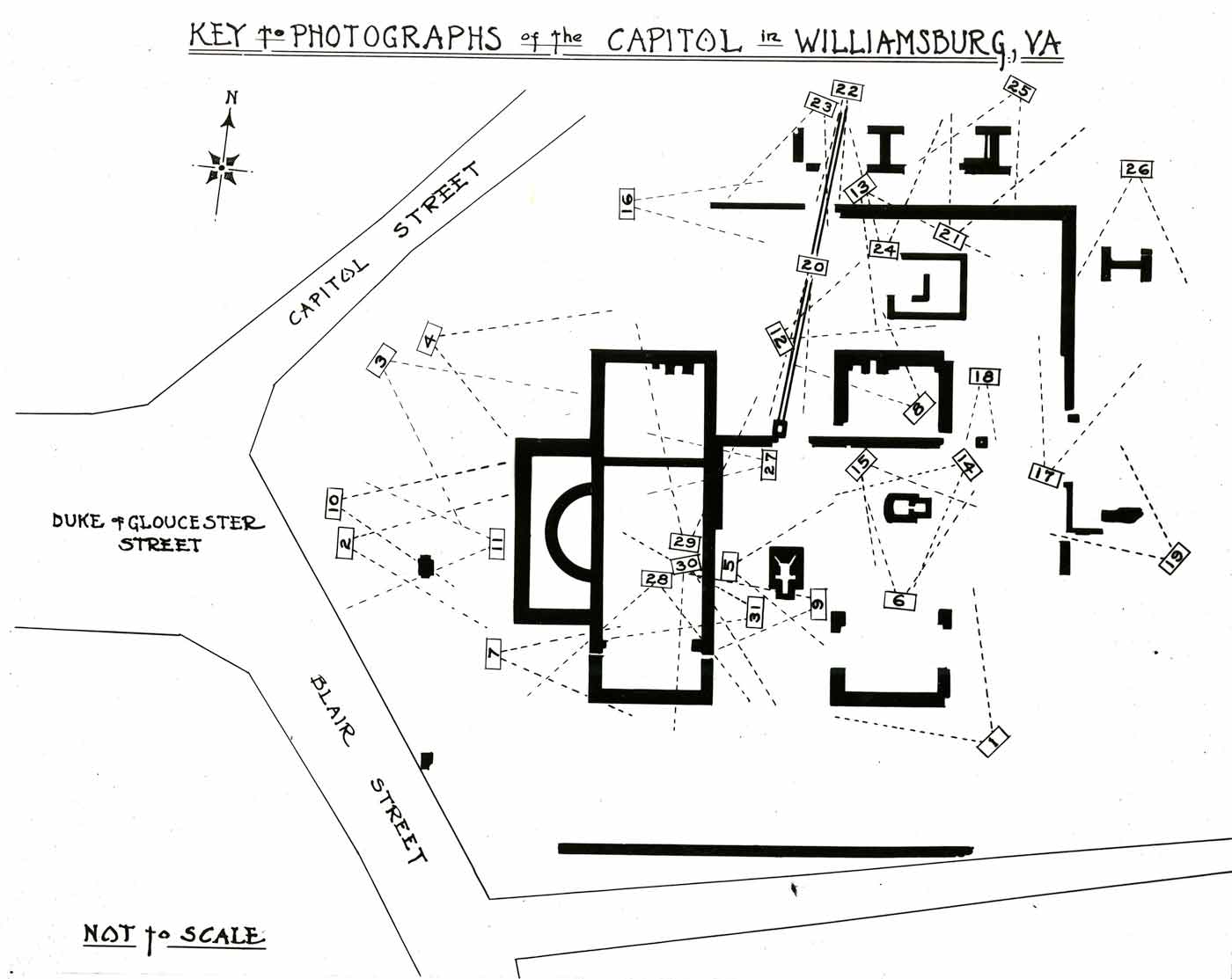

Layton worked closely with research staff to record the viewpoints required to properly document archaeological discoveries or steps in construction tasks. Several of the library’s archaeological drawings include diagrams showing the exact angles from which Layton’s photos were taken and are invaluable for understanding the viewpoints for today’s researchers.

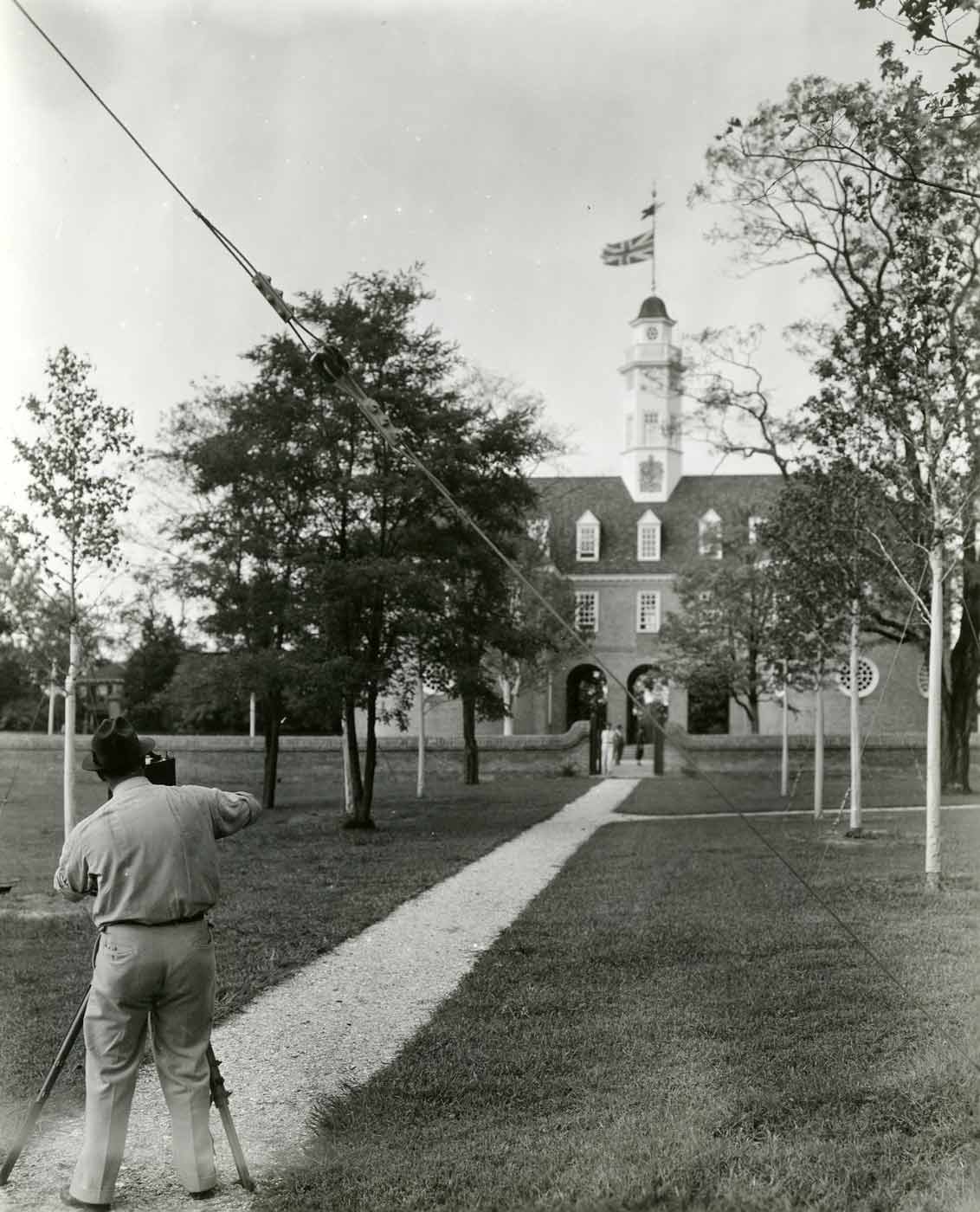

Frank Reginald Nivison, a photographer from the University Film Foundation at Harvard University, arrived in November 1930 and continued documentation of restoration work at each building site between 1930 and 1934. According to a memo issued by architect William G. Perry on December 12, 1930, his assignment was to “…include the photography of all buildings and parts of buildings, exterior and interior, which the architects deem necessary for architectural and historical purposes. Such photographs would be supplemented by progress photographs of construction work as it proceeds. All buildings to be wrecked should be photographed before wrecking takes place. In addition, there will be photographs of furniture, fabrics, and objects of all kinds.” Nivison established a studio at Bruton Parish House for developing photographs. Over the course of five years, he took more than 7,000 images and forwarded copies to the offices of Perry, Shaw & Hepburn where they compiled them into albums.

Once the initial phase of restoration work was completed, Colonial Williamsburg staff realized they needed to supplement record photography with aesthetically pleasing photos to attract visitors to the new historic site. Several photographers, including Ansel Adams, Samuel Gottscho, Wendell MacRae, and F.S. Lincoln, applied for the job of creating a photographic portfolio of Williamsburg buildings and gardens. F.S. Lincoln was ultimately awarded the position in 1935 due to his “…contact among important magazine editors and other outlets in New York City.” Many of Lincoln’s photos appeared in the December 1935 and November 1936 issues of the Architectural Record.

During this same period, Frank Nivison became the first official Colonial Williamsburg staff photographer between April 1934 and June 30, 1935 before opening an independent studio in Williamsburg in July 1935. He continued to photograph for Colonial Williamsburg on a contract basis, recording such events as the dedication of Duke of Gloucester Street, as well as the openings of individual exhibition buildings. By 1935, promotional photography had joined documentary photography to become an integral component of the visual history of the restoration.

Thus, between 1927 and 1935, the architects established a photographic archive which included all changes made in the historic city, as well as documenting progress and completion of every building and garden. An increasing number of images taken during the following decades grew to encompass costumed interpreters, programs, and visitors. Today the visual archives encompass half a million images. Housed at the Rockefeller Library, the collection continues to be actively used by researchers to understand the methods used to preserve and restore Williamsburg’s historic structures. One current example is the recently debuted Capitol 360 Virtual Tour which allows guests to toggle back and forth between modern day exterior and interior views and 1930s photos taken by Frank Nivison of the Capitol as it progressed through stages towards completion.

Colonial Williamsburg’s archaeology and architectural staff also regularly consult the photos before undertaking any new projects. The rich visual documentation in the archives continues to be a critical resource for understanding Colonial Williamsburg’s buildings and landscape, as well as for appreciating the immense undertaking behind Williamsburg’s restoration.

Resources

Dennis Montgomery, A Link Among the Days (Richmond: Dietz Press, 1998), 158.

Letter, Joseph W. Geddes to Perry, Shaw and Hepburn, November 7, 1931, Corporate Archives, John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library.

Letter, V.M. Geddy to Perry, Shaw and Hepburn, July 29, 1930, Corporate Archives, John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library.

Memo, Eileen Newman to Arthur L. Smith, April 12, 1962, Corporate Archives, John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library.

Letter, William G. Perry to Frank R. Nivison, December 12, 1930, Corporate Archives, John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library.

Letter, Bela W. Norton to Ansel Adams, March 7, 1935, Corporate Archives, John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library.

Draft letter, unknown to Frank R. Nivison, May 25, 1935, Corporate Archives, John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library.