The Story Behind the Story

In a previous post last July, we introduced the story of Margaret Hunter, one of Williamsburg’s milliners, who made and sold fashionable ornaments to accessorize both wardrobes and lifestyles. As an unmarried woman who owned her own shop, she represents an important example of one of many female entrepreneurs whose skill and keen business acumen helped to build a new nation. Through our interpretation of her shop today, we 21st-century milliners celebrate the often overlooked contributions made by her and the other working tradeswomen who made up a significant portion of the economy of early America.

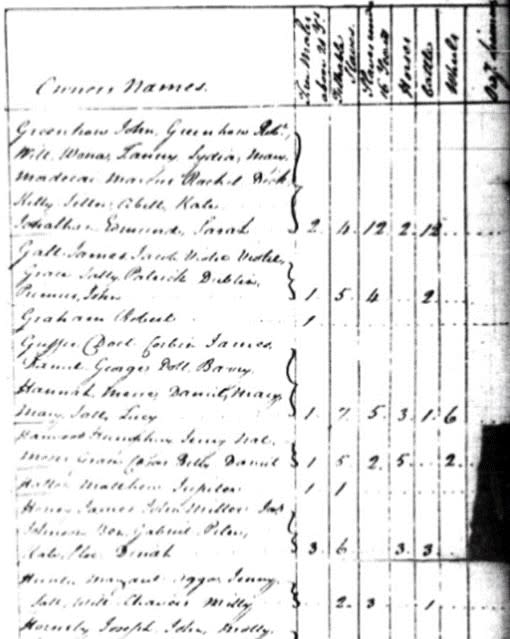

Yet it is vital to remember that there were a number of additional people who were also living alongside Margaret Hunter on the shop’s property. From the York county personal property tax records that survive for the years 1783, 1784, and 1786, we know that Hunter owned at least six enslaved people: Agga, Jenny, Milly, Sall, and Will (Billy) Chavers, as well as several unnamed children.

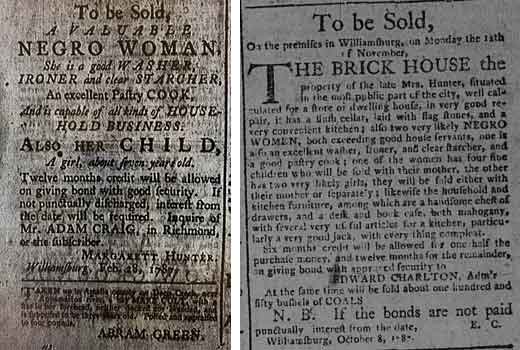

When interpreting the enslaved people who lived on Hunter’s property, our site has tended in the past to focus on the work they were believed to have performed. This is largely due to the fact that, aside from the property records, the only other available documentation about the enslaved community on the property are two newspaper advertisements offering several of the women and children for sale. In March 1787, Hunter placed her final advertisement before her death in the Virginia Gazette. Rather than touting goods for sale produced by her millinery business, it instead offered for purchase some of the enslaved individuals whose labor helped run that business. A subsequent notice appeared six months later, this one placed by Edward Charlton, Hunter’s brother-in-law and executor of her will, who sought to liquidate her assets following her death. In addition to the shop and real estate, a fine selection of mahogany furniture, and some kitchen goods, the ad also includes for sale two women and their six children. Together, these two advertisements give us the only glimpse we have into the daily reality that was life at Hunter’s millinery shop for the enslaved people who resided there.

What is immediately evident are the skill sets this small community of women collectively contributed: they are all “exceeding good house servants,” “capable of all kinds of household business,” and two of them are specified to be “an excellent washer, ironer, and clear starcher, and a good pastry cook.” Because sewing is not explicitly listed as a skill that any of them have, it has always been assumed that these women contributed behind-the-scenes labor that enabled Hunter to keep the shop running, but probably did not actively work within the business itself. After all, historians reasoned, having a knowledge of needlework of any kind would contribute further to their perceived “value” as enslaved labor, and thus would certainly have been stipulated in an advertisement for their sale. This assumption, however, seemed to be just that – an assumption – and we as 21st century historians wanted more documentation behind it before we would be comfortable continuing to perpetuate it in our daily interpretation.

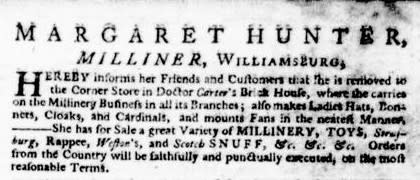

When Hunter advertised in the Virginia Gazette on June 21, 1771, she specifies that she “carries on the Millinery Business in all its Branches, also makes Ladies Hats, Bonnets, Cloaks, and Cardinals, and mounts Fans in the neatest manner.” What this implies is that while the “hats, bonnets, cloaks, and cardinals” represent the primary work of the millinery trade, other, closely related “branches” are often practiced in tandem. By exploring the specific skill sets associated with the trade and these branches, and by setting them side by side with the skills we know the enslaved women to have had, we quickly began to identify a number of similarities, leading us to suspect that the enslaved community at the millinery shop actually contributed much more directly to the day-to-day running of the shop and its public offerings than we had previously been led to believe.

Current scholarship suggests that not only fan-making, but also washing, ironing, and starching could have also been numbered amongst the branches of the millinery trade. Eighteenth-century dictionary definitions, want ads, and job descriptions found in servants directories and guidebooks for apprenticeships reveal a startlingly nuanced skill set encompassed under “washing,” laundry, and starching. For instance, English books on household management, which often describe the duties expected of each category of servant, consistently remind laundry maids of the necessity of completing all mending prior to washing. “As soon as any linen is left off, look it carefully over, and mend whatever little cracks or rents you may find, otherwise they will grow larger when they come into the water” (Sarah Phillips, The lady’s Hand-maid, London, 1758, p. 468). Mending is a highly skilled task, especially when it involves seamlessly adding new pieces of fabric to replace worn spots or re-weaving damaged sections of a textile through darning. The intricate handwork demonstrated on darning samplers (here’s one in Colonial Williamsburg’s collection (acc. no. 1971-1474)) attests to the well-practiced abilities required to perform this kind of refined work.

Starching would have been an essential part of the millinery business, as it involves the care of delicate, very fine fabrics that would have made up much of the stock of Margaret Hunter’s shop. Caps, ruffles, mitts, kerchiefs, aprons, and gentlemen’s neckwear were available ready-made. These offerings would have been “tumbled” daily by customers examining and trying on their options, and undoubtedly would have required washing and refreshing to keep them looking pristine until they were sold. The shop may have also offered washing and clear-starching as a service, like a drycleaner does today, and it would most likely have been an enslaved woman who performed that task. Mastering the use of starch – “a kind of paste made of flour or potatoes, with which linen is stiffened” (Thomas Dyche and William Pardon, A New General Dictionary, London, 1760) – translates logically to the art of the pastry cook, who likewise works with “paste” in the form of batter, pie crusts, and unbaked bread. Millinery shops were known to serve pastries to their customers as a shopping perk, making the skill doubly valuable to Margaret Hunter in building an upscale, profitable business with diversified offerings.

Even while we celebrate the entrepreneurial spirit of early American businesswomen like Margaret Hunter, it’s crucial to emphasize that there’s always a story behind the story, which, once uncovered, often reveals itself to be a large part of the true story itself. The information that we’ve been accumulating about the details of the millinery trade, its branches, and knowledge base is not just transforming how we think about the trades themselves and how they were practiced. More vitally, it’s also changing the way we think about who practiced the trades, how those services were performed and offered, and how they helped to define the community that was Williamsburg on the eve of Revolution.

This fall, join us for “Voices of Their Hands,” a walking tour discussing the lives of enslaved tradespeople. Hear Historic Trades people discuss their experiences interpreting skilled laborers and their work. Get your free reservation here.

We would like to say thank you again to the incomparable staff at the Rockefeller Library, who always go above and beyond to assist us in our research quests.

Journeywoman milliner and mantua-maker Rebecca Starkins joined the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation full time in 2016. Her research interests include puzzling out the intricacies of outerwear styles and examining representations of working women in 18th- and 19th-century literature by female writers.

Mistress milliner and mantua-maker Janea Whitacre, after 39 years, is still using her Art History degree every day as she continues to discover more and more about her 18th- century trades. When not at work, she and her husband can be found traveling with their little vintage Airstream trailer going from one costume exhibit to the next.

Colonial Williamsburg is the largest living history museum in the world. Witness history brought to life on the charming streets of the colonial capital and explore our newly expanded and updated Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, featuring the nation’s premier folk art collection, plus the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670–1840. Check out sales and special offers and our Official Colonial Williamsburg Hotels to plan your visit.