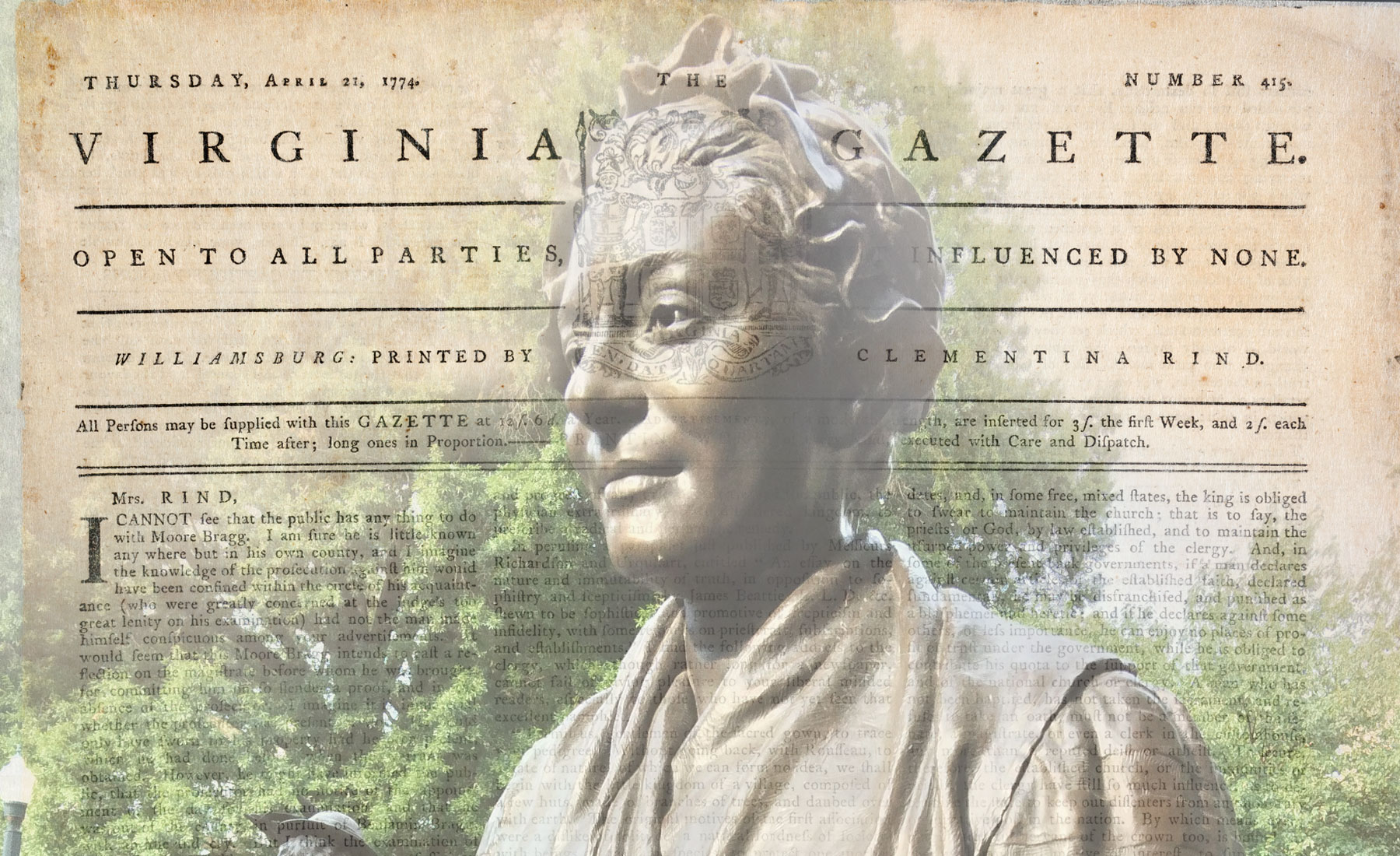

There are some surprising things in the pages of the Virginia Gazettes.

The Virginia Gazettes are full of unexpected stories. As the first newspaper (and the second, third, and fourth) published in Virginia, the Virginia Gazettes offer one of our richest windows into the stories that Colonial Williamsburg tells. Read more about their history below, and explore their issues through the digital collections of the Colonial Williamsburg’s John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library.

Couldn’t they think of another name?

Each of these papers was named the Virginia Gazette.1 There were other Virginia Gazettes published in Williamsburg during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries as well. So why were Virginia’s printers so unimaginative?

In fact, Virginia’s politicians were probably more to blame than its printers. Numerous colonial laws required the government or its subjects to place advertisements in the Virginia Gazette. In 1762, for example, the colony’s legislature passed a law requiring anyone recovering a stray animal to advertise about its recovery “four times in the Virginia Gazette.”2 Legislators also ensured that some laws were published in the Gazette.3

Given these requirements, publishers might have worried that if their newspaper was named the Virginia Journal, for example, they might no longer be an appropriate venue for these legally-required public notices.4 The result was several distinct Virginia Gazettes—and many generations of confused historians.

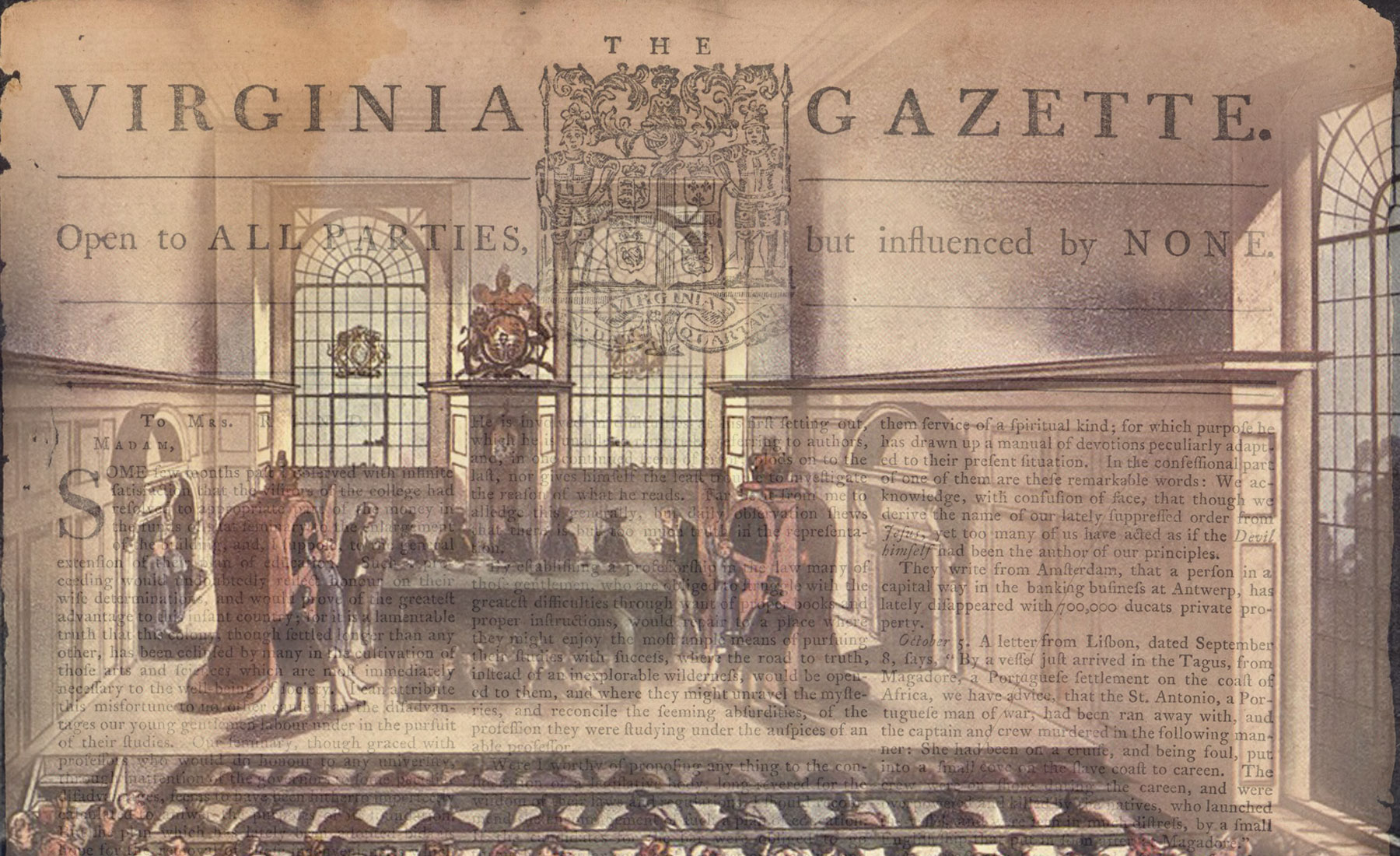

Who read the Virginia Gazette?

Not everyone could afford to subscribe to the Virginia Gazettes. A year’s subscription to any of the Gazettes cost the same price: twelve shillings, six pence.5 That wasn’t a fortune, but it also wasn’t a pittance. For an unskilled laborer, that was about a week’s wages.6

While subscription records for the Gazette have not survived, one historian has calculated that based on the amount of paper William Hunter purchased each week in 1751, he published about 960 copies.7 These subscribers would have predominantly been prosperous white men at the head of their household.8 Subscribers would have included the colony’s elite, such as plantation owners, merchants, lawyers, and government officials. Though more than half a million people lived in Virginia near the end of the eighteenth century, only small minority of them would have subscribed to one of the Gazettes. 9

But copies of the Gazettes floated around town. When someone finished their copy, they shared it.10 If no one in your household subscribed to the paper, you might be able to find one at a local tavern or coffee house.11 Some non-subscribers even stole the news. A year after the Gazette was first published, William Parks complained that people who were “desirous of News, but are too mercenary to pay for it” were stealing copies of the Gazette that were in transit to paying customers.12 Even if they couldn’t afford a subscription, people in the eighteenth century could be quite resourceful at getting their hands on the news.

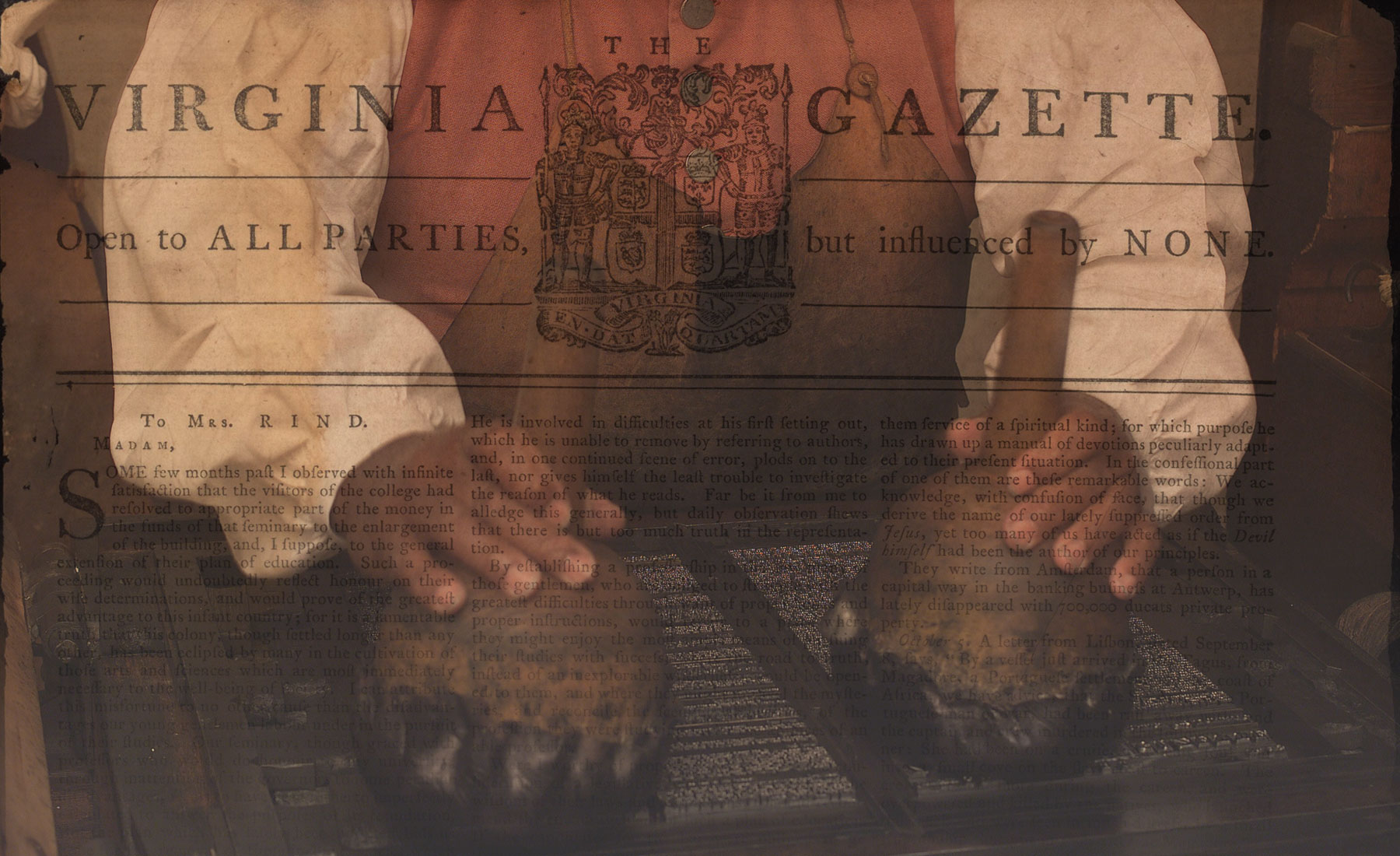

How was the Gazette printed?

The process for printing an eighteenth-century newspaper was manual and labor-intensive. Watch this video from Colonial Williamsburg’s print shop to learn more.

What did the Virginia Gazette publish?

Many of the Virginians who led the American Revolution would have been regular readers of the Virginia Gazettes. What would they have read in its pages?

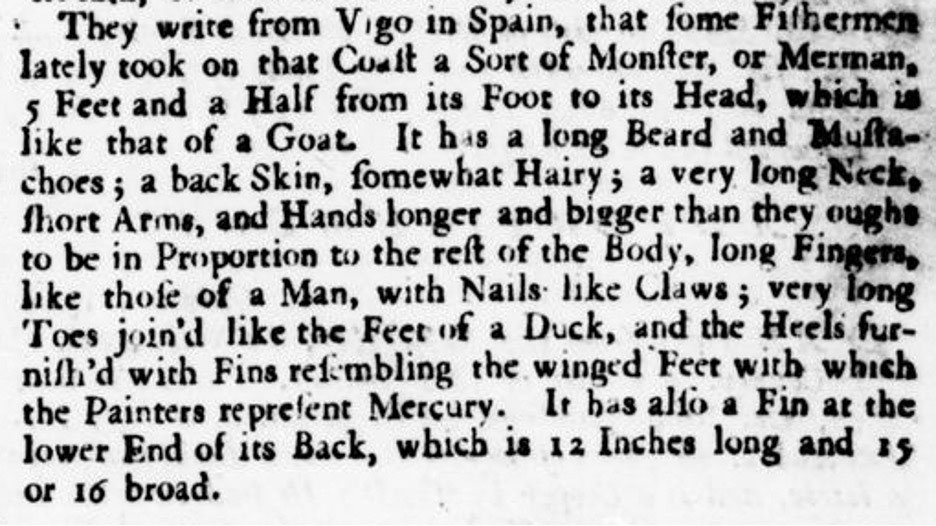

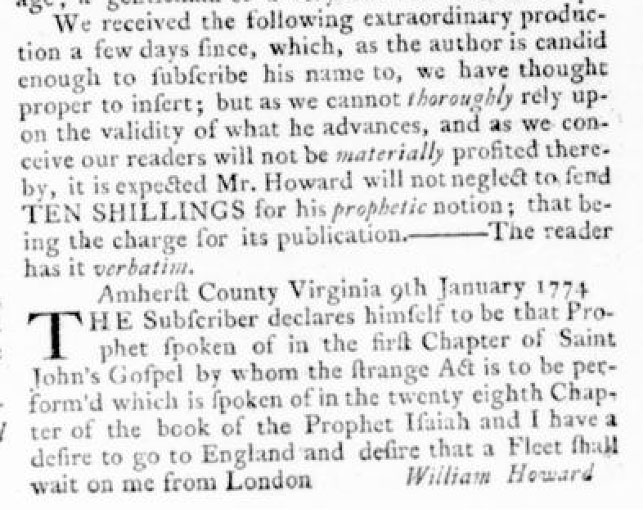

If you open a copy of the Virginia Gazette, the first thing you’ll notice is that there is very little coverage of local events. Since Williamsburg was a small town, news traveled quicker on the street than in a weekly publication. Instead, like other eighteenth-century North American newspapers, the Gazette published a great deal of news about Europe and the Caribbean, often weeks or months after the fact.13

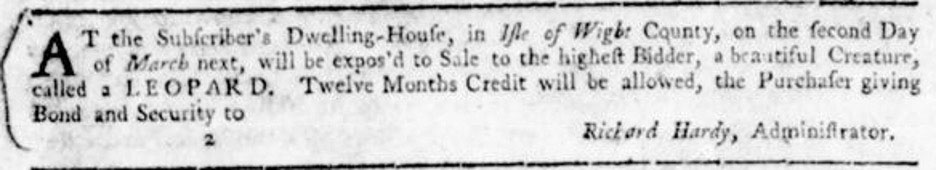

Though its news sections focused on faraway places, the Virginia Gazette published countless advertisements, essays, and poems from local authors. Its advertisements document the minutiae of everyday life in early Virginia like few other sources.

Thousands of advertisements offered to buy or sell enslaved people. Thousands more attempted to recover a self-emancipated enslaved person. These notices are one of our best sources for understanding the lives of enslaved people and the economics of the slave trade.

Go Deeper

The Virginia Gazettes intimately document how the American Revolution unfolded in one of the cities that ignited it. Dive in to the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library’s collection, or check out the links below.

Virginia Gazette Resources

Stories of Women from the Virginia Gazettes

Slavery & The Virginia Gazette

Sources

- Many eighteenth-century British colonial newspapers imitated the authoritative London Gazette by following the city or colony’s name with “Gazette.”

- William Waller Hening, ed., The Statutes at Large: Being A Collection of all the Laws of Virginia, from the First Session of the Legislature, in the Year 1619 (Richmond: Franklin Press, 1820), 7:547. See also ibid., 5:221, 5:561, 6:225, 6:365, 6:554, 7:289, 7:547–48, 8:214, 8:356, 8:359, 9:68, 9:204.

- Hening, ed., Statutes at Large, 8:250.

- See also David Copeland, “America, 1750–1820,” in Hannah Barker and Simon Burrows, eds., Press, politics and the public sphere in Europe and North America, 1760–1820 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 148.

- An eighteenth-century newspaper’s masthead, which is at the top of the first page, or the colophon, which appears at the very bottom of the last page, usually recorded the subscription rates for the Virginia Gazettes. See, for example, the masthead of Virginia Gazette (Pinkney), Jan. 5, 1775, page 1; colophon in Virginia Gazette (Purdie), Feb. 3, 1775, page 4; masthead of Virginia Gazette (Dixon and Hunter), Jan. 7, 1775, page 1. Note that issues for the Gazette would not have been sold individually.

- Thomas Jefferson’s accounts for 1796–1797 list payments of two shillings six pence for a laborer’s work. Such a laborer would have had to work for five days to pay for a Virginia Gazette subscription. History of Wages in the United States from Colonial Times to 1928 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1929), 55. See also Donald R. Adams, Jr., “Prices and Wages in Maryland, 1750–1850,” Journal of Economic History 46, no. 3 (Sept. 1986): 633; Jordan E. Taylor, “Circulation, Subscription, and Circumscription: The Pennsylvania Journal and Newspaper Readership in Revolutionary Philadelphia,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 146, no. 2 (April 2022): 134–160.

- Charles E. Clark, The Public Prints: The Newspaper in Anglo-American Culture, 1665–1740 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 201.

- While no subscription record for the Gazette has survived, the University of Virginia holds a collection of account books for some of the Gazette’s printers. See “Virginia Gazette Daybooks,” University of Virginia Library,

https://search.lib.virginia.edu/sources/uva_library/items/u2435677?idx=0&page=3 (accessed Jan. 12, 2024). - If Hunter did serve about 960 subscribers in 1751, then his Virginia Gazette probably reached less than 4% of the colony’s population (considering that many of those subscribers were out of state). On newspaper subscribers in early America, see Parkinson, Common Cause, ch. 1; John L. Brooke, Columbia Rising: Civil Life on the Upper Hudson from the Revolution to the Age of Jackson (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 2010), 122–27; Charles G. Steffen, “Newspapers for Free: The Economies of Newspaper Circulation in the Early Republic,” Journal of the Early Republic 23 (Autumn, 2003): 381–4190. Note that the Virginia Gazette circulated beyond Virginia. In 1777, for example, the North-Carolina Gazette published an advertisement from a newspaper sales agent that named (and shamed) 24 North Carolina subscribers to the Virginia Gazette whose payments were overdue. In a study of these subscribers, D. L. Corbitt identified most of them as government officials, soldiers, and men of influence. Advertisement signed Richard Cogdell, North-Carolina Weekly Gazette (New Bern), Aug. 8, 1777, p. 4; D. L. Corbitt, The North Carolina Historical Review 6, no. 4 (Oct. 1929): 422–423n42–67. Some Virginians also read newspapers published elsewhere. The subscription book for the Pennsylvania Journal, published two hundred miles away in Philadelphia, records seven subscribers in Williamsburg. Parkinson, Common Cause, 706.

- Richard Brown, Knowledge is Power: The Diffusion of Information in Early America, 1700–1865 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989), 147.

- David W. Conroy, In Public Houses: Drink and the Revolution of Authority in Colonial Massachusetts (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1995), 234–35.

- “To the Subscribers for the Virginia Gazette,” Virginia Gazette, July 29, 1737, page 4.

- Charles Clark found that about only about a fifth of the news content published in the Pennsylvania Gazette from 1723 to 1765 concerned British North America. See Clark, Public Prints, 216.