On October 22, “I made this….”: The Work of Black American Artists and Artisans opened to the public at the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg. The exhibition brings together objects made by Black American artists and artisans, celebrating three centuries of craftsmanship. Over 25 pieces, from paintings to furniture to ceramics to textiles, are on view, a third of which are new to Colonial Williamsburg’s collections.

Colonial Williamsburg has long been committed to African American history. In 2020, the Foundation celebrated 40 years of African American interpretation. Objects made by Black craftspeople have been collected for at least 75 years and the Foundation continues to be a leader in organizing important exhibitions on Black-made material culture, like an important show of African American quilts and an early exhibition on Joshua Johnson, one of the earliest professional free Black portrait painters in America. The Art Museums’ latest show continues to make history as the Foundation’s first multi-disciplinary exhibition to present the many rich stories surrounding these talented American artisans and craftspeople.

Keep reading to learn about four recently acquired objects that are now on view in the “I made this…”: The Work of Black American Artists and Artisans exhibition and visit us in person to see these important pieces.

One of our newest acquisitions is this stylish chair by renowned Black cabinetmaker, Thomas Day, that descended through the Watkins family until it was given to Colonial Williamsburg in early 2022. Day was born to free Black parents in 1801 and successfully navigated life as a free person of color in antebellum North Carolina, where he established his own cabinetmaking shop producing furniture and architectural woodwork until his death in 1861.

Also in 2022, the Foundation acquired these fashionable sugar tongs that are marked by Peter Bentzon, a free man of color who worked as a silversmith throughout the first half of the 19th century. Born in the Danish West Indies, he completed an apprenticeship in Philadelphia before returning to the Caribbean where he operated a silver business in Christiansted, Saint Croix. Bentzon returned to Philadelphia frequently for business and eventually opened a shop there in the 1820s. He is the only free person of African ancestry from the antebellum period in the United States whose works in silver can be identified through his own hallmarks.

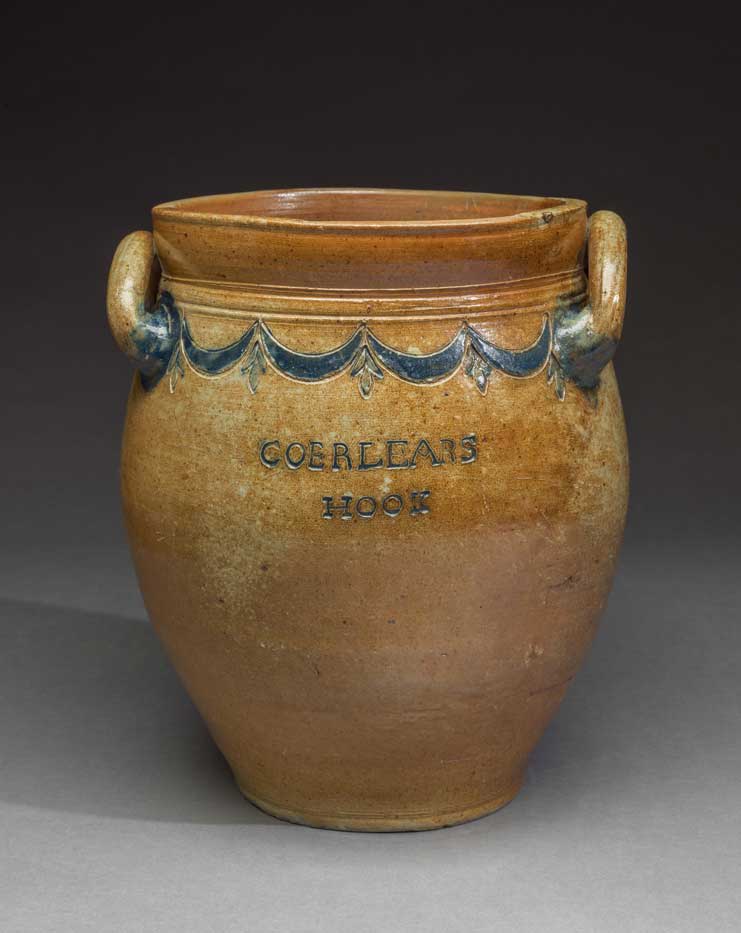

Thomas Commeraw, a free Black potter, established his own stoneware kiln on the East River in Manhattan at Corlear’s Hook in 1797. Last year, Colonial Williamsburg purchased this impressive storage jar attributed to his kiln. Commeraw operated his business until 1819, after which he moved to Sierra Leone as part of the American Colonization Society, a group founded to support the migration of free people of color to the continent of Africa. Commeraw was a leader within this new colony, documented by his surviving letters that expressed his hopes for the project.

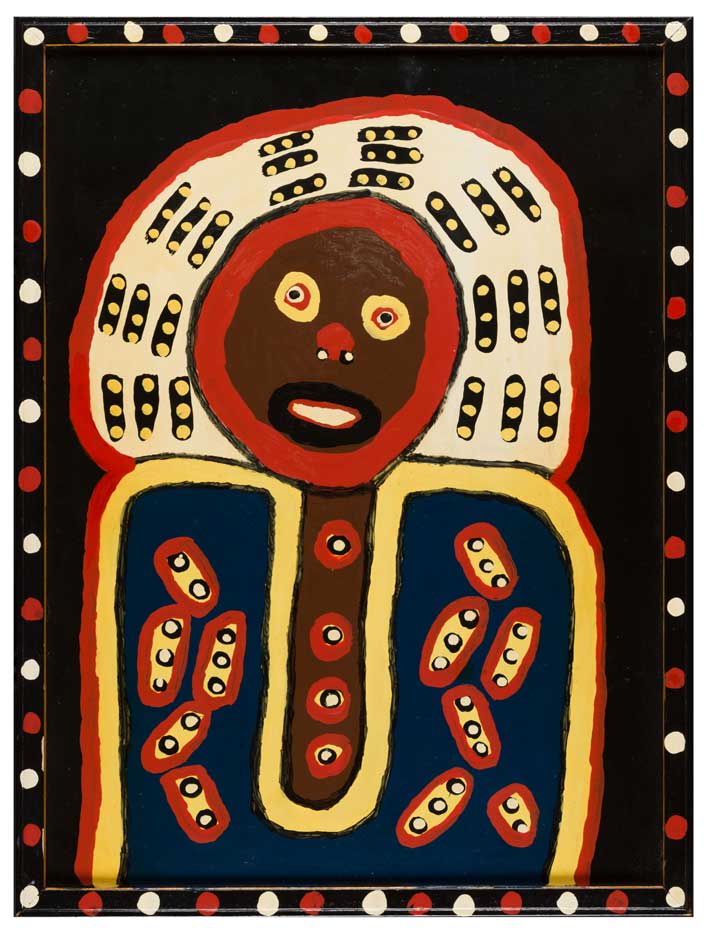

Richard Burnside turned to art to help deal with the pain left by a foot injury that ended his military career. His imaginative, expressive works were painted in a heavy, stylized way that quickly became popular among the burgeoning outsider art world of the 1980s. Burnside, however, preferred to paint for the people of his small town of Pendleton, South Carolina, making works based on his own self-styled Africanized mythology and other subjects that would make them happy. Burnside painted on gourds, cardboard, plywood, and anything else he could find so that he could share his work with anyone and everyone who was interested.

These are just some of the many pieces you will see in our newest exhibition. Next time you're at Colonial Williamsburg, we invite you to visit the Art Museums and see the craftsmanship and artistry of these beautiful pieces for yourself.

Colonial Williamsburg is the largest living history museum in the world. Witness history brought to life on the charming streets of the colonial capital and explore our newly expanded and updated Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, featuring the nation’s premier folk art collection, plus the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670–1840. Check out sales and special offers and our Official Colonial Williamsburg Hotels to plan your visit.