Shopping for a New Gown in the 18th Century

Getting new clothing in the 18th century was much more of a participatory process than it is today. Mantua-makers — dressmakers — used a process called “cutting to the body” to create most fitted clothing for women. Before mass-produced clothing, standardized sizing, or commercial patterns existed, fitted garments were made to each and every individual, regardless of socio-economic status. Fabric was laid against the body, folded, tucked, and smoothed around the form, and each shape cut right against the customer. This meant that you were literally in the middle of the process of having your clothing made right around you. Details of style, fit, and design came under your scrutiny before any final decisions were made. A process that is limited today to a couture price tag was standard of industry to 18th-century dress shoppers. Not bad, eh?

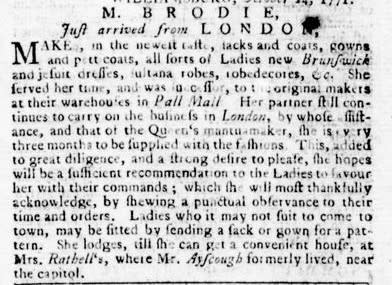

But what if you lived too far from a city to have new clothing made as frequently as you might like? Or what if you, like Martha Washington, you preferred a London mantua maker to a Virginian one? While cutting to the body itself was the ideal process because it allowed for the most accurate fit and permitted the customer to have a say in the finished product, there were alternative methods available. A lady might, for example, send a pair of her stays, from which a skilled mantua maker could gather all of the information necessary to cut a gown. Or, she might also send an old gown to be used as a “pattern.” Margaret Brodie, one of Williamsburg’s mantua makers, advertised this service for “ladies who it many not suit to come to town.”

As part of our research into and preservation of the 18th-century trade, this is a skill we continue to train for today as apprentice mantua makers at Colonial Williamsburg. Recently, I was challenged to copy a sack gown that had been made over a decade ago in the shop for a lady who is no longer on staff. As luck would have it, though, it just so happened to also fit our “Martha Jefferson” very well, so she was enlisted as our model, with the promise of a new gown as compensation for her generous assistance in the project. Without being able to take the original gown apart, the goal of the exercise was to make a new gown to fit the model in precisely the same way. Even the careful eye of our shop mistress had to admit that the finished product came out quite well and mirrored the fit of the original right down to every minor wrinkle and fold!

Apprentice milliner and mantua-maker Rebecca Starkins joined the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in 2016. Her research interests include puzzling out the intricacies of outerwear styles and examining representations of working women in 18th- and 19th- century literature by female writers.