Bringing a Portrait to Life

Have you ever wondered what goes on behind the scenes to bring you some of Colonial Williamsburg’s signature program offerings? Where do the ideas come from? Why do we make the choices that we make? What does each presentation aim to convey and achieve? Every program has its own complex history of inception, evolution, and realization. Here’s just one of those many stories.

Every December during the week after Grand Illumination, the millinery shop presents a three-day program in which we create a wedding ensemble of the 1770s. In the tradition of the 18th-century mantua-making trade, the gown is typically cut directly to the body of our bride, allowing us to ensure a perfect fit and the lady to oversee all stylistic details. With COVID-19 not only preventing us from standing within six feet of our “customer,” but also limiting our consecutive interpretive time to one day a week in a space not our own, we had to get creative to ensure that our favorite annual program could still be offered for holiday visitors. In the end, our pandemic parameters helped us reimagine the program as something completely new and quite different from anything we’ve done before.

When Colonial Williamsburg reopened in mid-June 2020, I was just about to begin the fifth and final level of my apprenticeship in millinery and mantua-making. In our shop, this culminating level consists of three “capstone” projects intended to demonstrate not only the apprentice’s mastery of the skills of the trades, but also a familiarity with scholarship in the discipline, the ability to interpret their work in formal and informal contexts across various platforms, and an understanding of current practices and methodologies within the wider fields of museum studies and public history. One of these final projects requires the apprentice to develop and implement an advertised program which also requires supervising the shop’s work team to produce a three-dimensional realization of clothing from an 18th-century portrait. Knowing that we had our wedding program looming on the horizon and realizing that our pubic interaction time would be minimized because of the pandemic, the Mistress of the shop decided to combine the two programs and left it to me to determine the precise form the 2020 wedding gown would take. Enter Maria Walpole.

The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond owns a portrait of Maria Walpole, the Duchess of Gloucester, painted by Nathaniel Dance-Holland between 1766 and 1769 (acc. no. 60.36). Her gown had long been on my “one day to make” list for its understated elegance and delicate aesthetic effect in perfect proportion. A prominent figure in English society, Maria’s fashion choices were highly visible and widely admired. It’s no coincidence that she had her portrait painted numerous times by many of the most fashionable portraitists of the day. There was also the added attraction of deciphering the silk cloak draped on the table at her side. Outerwear has been the focus of much of my personal research over the past few years, so the opportunity (read: excuse) to make (yet another) cloak with such a curious edging was appealing. And, of course, the intrigue of her personal connection to one of the trades that we practice in our shop certainly couldn’t be ignored: Maria was the illegitimate daughter of Dorothy Clement, a London milliner, and Edward Walpole, son of the first Prime Minister of Great Britain. In 1766, she married Prince William Henry, Duke of Gloucester and Edinburgh, one of the brothers of King George III. The marriage was kept secret until 1772 and apparently displeased the king, who never welcomed her to court.

The 1766–1769 date range of the Dance-Holland painting suggests that this could be a wedding portrait, but the date is really the only indicator of that possibility. Don’t let the color of the gown fool you! White was not yet traditional for wedding wear. Queen Victoria’s choice to wear a white dress for her marriage ceremony in 1840 is generally accepted to have inaugurated the trend, though it wasn’t until the 1950s that it became the dominant bridal preference in Anglo-American culture. Maria’s white gown most likely reflects a choice of the season’s trending color, rather than any kind of bridal status. To an 18th-century lady, getting married was simply an excuse to acquire a new fashionable dress in whatever color or style she chose; afterward, the “wedding gown” would be integrated into her everyday wardrobe. In the ten years the millinery shop has been hosting this program, we’ve never made a white gown specifically because we wanted to invite a conversation about the little-known history behind the “wedding white” tradition. This year, however, we decided to meet modern expectations for the first time by producing a white gown and share the unexpected story behind how that tradition came to be.

Another reason why Maria’s portrait was an ideal choice for both a culmination project and our wedding program was that seamlessly integrates (pun intended!) the two trades that make up our dual apprenticeship of mantua-making (dressmaking) and millinery. The portrait’s millinery — the ornaments like the excessive “treble” lace elbow ruffles, lace collar, hair decoration, and cloak on the table beside her — elevate the level of formality of the gown from what the 18th century would call “fashionable undress” (casual but stylish daywear) to a “half dress,” or semiformal ensemble. Specific wedding millinery was known to have been sold by several of the milliners in Williamsburg and was one way a bride might accessorize a gown to make it a little more special for “her day of days.”

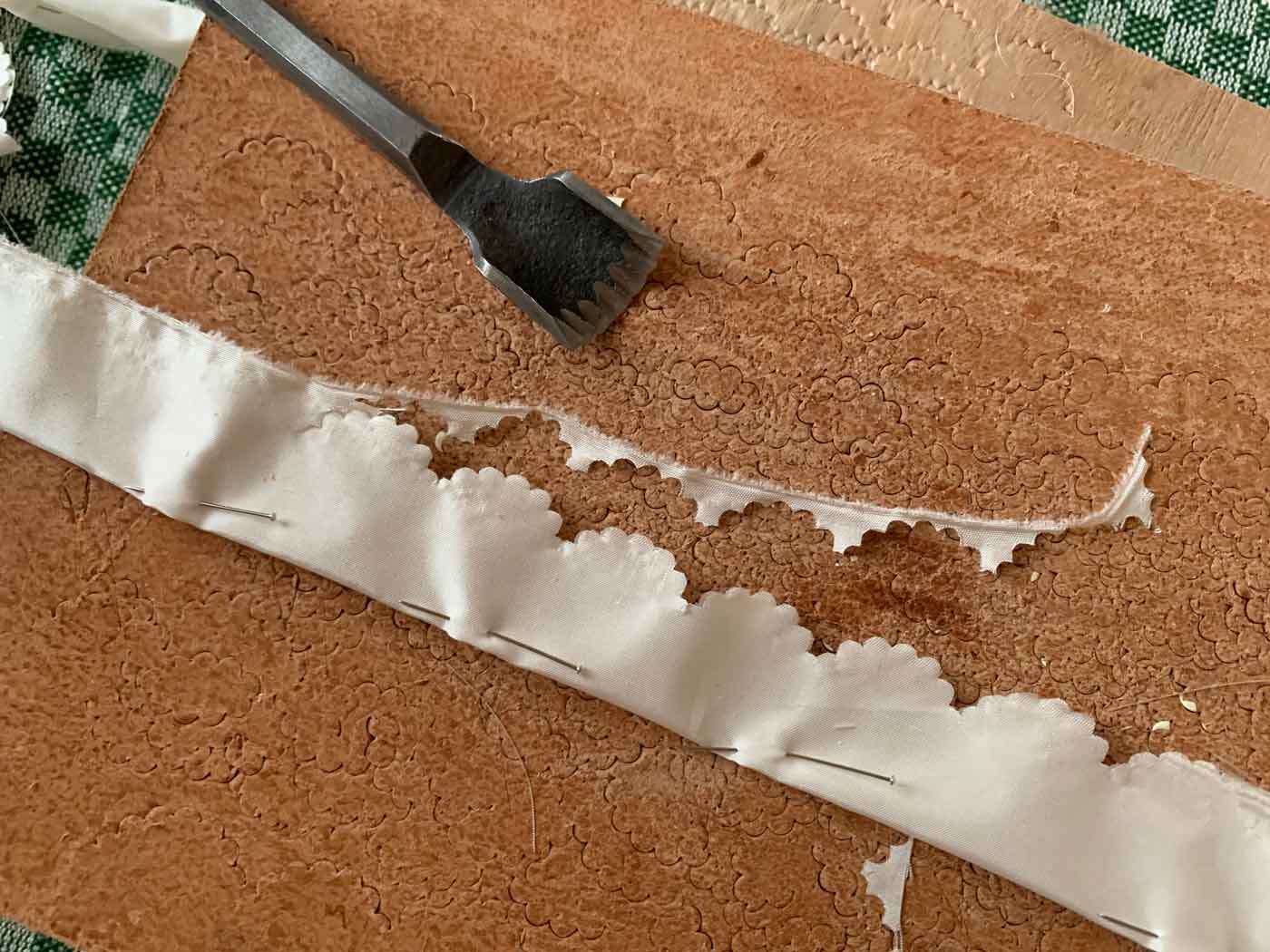

With only four days and three pairs of hands to cut and hand stitch everything, we had to be strategic about dividing the labor and using our time efficiently, just as our historical counterparts would have done. The gown itself required about 15 hours to complete, which is a little longer than average. Mantua-making typically cuts a gown directly to the body of the customer, laying fabric against her stays and sculpting and trimming it to shape; a sack gown like Maria’s made using this method can usually be completed, start to finish, in about 12-14 hours. However, because COVID-19 precautions prevented us from being close enough to someone else to do this, we had to employ the 18th-century long-distance alternative, which involves cutting a gown using an old gown as a stand-in for the customer’s body. Over the past year, we’ve become quite proficient at this approach and find that it produces successful results, although it does take longer in the cutting. The trim, which was pinked using a scallop-edged chisel, took an additional 45 hours to cut, finish, gather, arrange, and stitch to the gown.

Despite this being “my” final project, it was important to me to use this program as an opportunity to bring together and showcase the incredible knowledge and work of some of my colleagues throughout Colonial Williamsburg. Did you happen to notice Maria’s earrings and the bow at her neck? One of our silversmiths, Chris, examined their details and concluded that they were most likely cut steel, a fashionable alternative to precious metals and stones that achieved a similar sparkling effect. Yes, even the 18th century appreciated a quality knock-off! The books in Maria’s hands? Bound by our bookbinders and selected to match the portrait’s proportions as closely as possible. How about the table on which the cloak is draped? I asked our Master Cabinetmaker whether this type of piece had anything like standardized measurements in the 18th century. Little did he know that what I was really after was a height measurement I could use to calculate the appropriate proportions for the trim on the gown and petticoat and obtain a hint about the style of the cloak based on how much was draped over the edge!

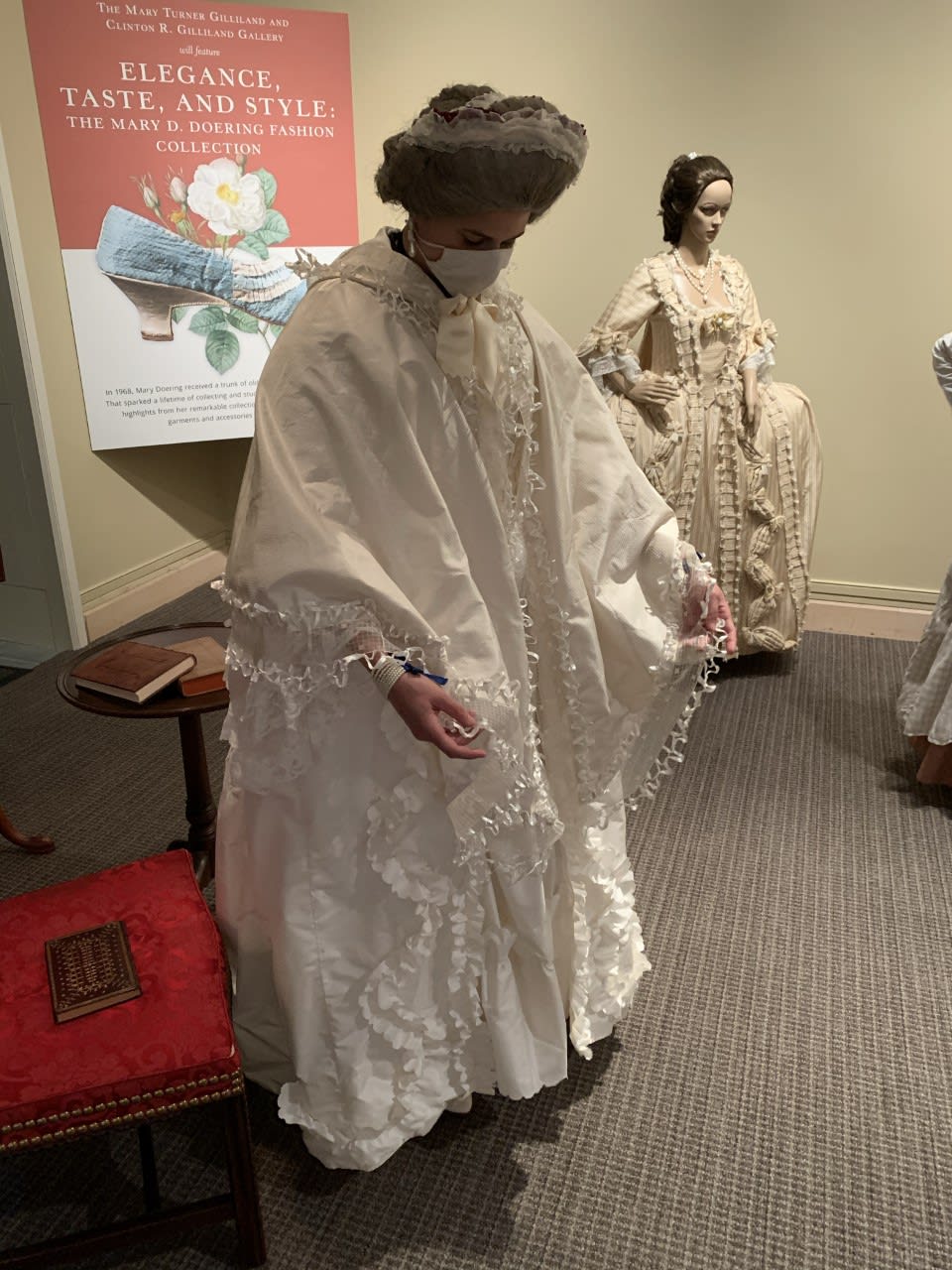

When it comes down to it, though, the final look would never have been as effective without two other individuals. Maria’s hair in the portrait is almost certainly her own; by the third quarter of the 18th century, most women chose to dress their hair, rather than wear a wig. A regimen of pomatum and powder — essentially equivalent to a dry conditioner and shampoo — helped to keep the hair healthy and clean, and contributed to the softened color and matte finish that can be seen in many portraits. Because our model Maria’s modern haircut is too short to be styled as her counterpart wore it, Edith, one of our wigmakers, recreated the fashionable style using a cushion beneath to achieve the coiffure’s ever-ascending height at the dawn of the 1770s. “Maria,” played by actor-interpreter Michelle Smith, pulled it all off beautifully. While we put the finishing touches on the gown around noon on our fourth and final day, she regaled the audience with Maria’s personal history and explained the process by which clothing like hers would have been acquired. Once everything was in place from head to toe, she took her place beside the painting.

Pairing a portrait with its three-dimensional recreation also enabled us (almost literally!) to stitch together the all-too-often segregated spaces of the traditional and the non-traditional museum. To celebrate the completion of newly expanded gallery space, the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg are exploring more experiential museum experiences. One exciting new initiative invites tradespeople from the Historic Area to work alongside the antique pieces that they strive to recreate daily. Taking the practice of a trade outside of its 18th-century “living history” tableau and inserting it into a modern gallery environment makes visible for visitors the methodology that defines much of our work, as we examine extant items to understand how they were made. At the same time, it breathes life into static antiques, reminding visitors that the objects they view in curated gallery cases are the representation of skilled individuals’ artistic vision, the products of unique makers’ hands.

Special thanks to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts for the opportunity to focus this program on their portrait.

Journeywoman milliner and mantua-maker Rebecca Starkins joined the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in 2016. Her research interests include deciphering the intricacies of outerwear styles and examining female writers’ representations of working women in 18th- and 19th-century literature.

Colonial Williamsburg is the largest living history museum in the world. Witness history brought to life on the charming streets of the colonial capital and explore our newly expanded and updated Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, featuring the nation’s premier folk art collection, plus the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670–1840. Check out sales and special offers and our Official Colonial Williamsburg Hotels to plan your visit.